DEVELOPING A COMPREHENSIVE MODEL FOR ENHANCING RURAL LIVELIHOOD THROUGH AGROFORESTRY PRODUCTS

-Dr. SP Singh1 Mr Abhi Bose Haldar2

ABSTRACT

This study is an outcome of the Summer Internship carried out with PRADAN, conducted in Katoria block of Banka district, Bihar, explored the design of a comprehensive livelihood model aimed at enabling small and marginal farmers to achieve an annual income of 2.5 lakh through integrated agricultural and allied activities. The study focused on the Agriculture Production Cluster (APC) approach, emphasizing collective action and resource optimization. Fieldwork was carried out in six villages-Inaravaran, Lilavaran, Letwa, Sikatvaran, Uparchakmadia, and Giddhmarwa-where surveys were conducted with 82 households, of which 50 progressive farmers were selected for detailed analysis using stratified sampling. Both primary and secondary data have been used in the study. The data collection was based on the landholding patterns, crop cultivation practices, livestock ownership, fodder management, and engagement in allied livelihoods such as goat rearing, backyard poultry, and tasar silk. An attempt has also been made to assess the role of women farmers and potential agri-entrepreneurs, highlighting their contributions and identifying gaps in credit access, training, and market linkages. The study reveals that there was a significant variation in landholding size, income levels, and diversification strategies across villages, with goat rearing, poultry, and vegetable cultivation emerging as viable options for scaling up. The proposed livelihood framework integrates crop production with livestock and forest-based resources to ensure income diversification, resilience against climate risks, and sustained productivity. This study recommends and promotes improved farming techniques such as System of Root Intensification (SRI), Integrated Pest Management (IPM), green fodder cultivation, and strengthening Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) for collective input procurement and market access. The study highlights the importance of participatory engagement, gender-sensitive planning, and convergence with government schemes to address rural livelihood challenges. The insights gained contribute to PRADAN’s mission of building inclusive, sustainable, and community-driven development pathways for rural households in tribal and resource-constrained regions of Bihar.

INTRODUCTION:

Rural livelihoods in Bihar, particularly in tribal areas such as Katoria block of Banka district, are largely dependent on smallholder agriculture and allied activities. However, fragmented landholdings, low productivity, poor irrigation, and weak market linkages create persistent challenges, forcing households to rely on livestock rearing, wage labor, or migration to sustain themselves. To overcome these barriers, PRADAN has introduced the Agriculture Production Cluster (APC) model, which focuses on collectivizing small farmers, integrating crops with livestock and allied activities, and linking them to markets and institutions. This approach enables economies of scale, reduces risks, and creates opportunities for sustainable income growth. Studies on rural development highlight the importance of diversification through goat rearing, backyard poultry, and tasar silk cultivation, which provide quick returns and improve resilience. Women play a central role in these enterprises, particularly through Self-Help Groups (SHGs) and Village Organizations, which enhance both financial inclusion and decision-making power. The internship was carried out in six villages of Katiyari Panchayat to assess existing livelihood systems, identify gaps, and propose an integrated livelihood framework.

LITERATURE REVIEW:

Rural livelihoods in India, especially in tribal and semi-rural regions such as the Katoria block of Banka district, Bihar, are predominantly dependent on smallholder agriculture, livestock rearing, and allied activities. Research consistently highlights that fragmented and marginal landholdings-often less than one acre-limit productivity and mechanization, forcing households to rely on diversified strategies to sustain themselves (Birthal et al., 2007). Goat rearing, backyard poultry, and tasar silk cultivation have been recognized as low-investment yet high-return options that complement agriculture and provide a buffer against crop failures (Singh & Chauhan, 2015).

Goat rearing has been widely described as the “poor man’s cow,” owing to its adaptability and accessibility for smallholders. Studies on breeds such as Black Bengal and Jamunapari demonstrate their profitability, reproductive efficiency, and role in enhancing household cash flow (Kumar et al., 2003).

Backyard poultry, particularly using indigenous breeds, has been documented as an important source of quick income and nutritional security, with women playing a central role in management (Ahuja & Sen, 2007). Similarly, tasar silk cultivation is deeply embedded in the livelihood systems of tribal communities in Eastern India, providing seasonal employment and value addition opportunities when linked to strong institutional support (Choudhury & Jena, 2011). Women’s participation in Self-Help Groups (SHGs) and Village Organizations (VOs) has also emerged as a critical driver of inclusive growth. NABARD (2018) highlights that SHG-based interventions improve access to credit, strengthen market linkages, and enhance women’s decision-making power. NDDB (2020) notes that women-led poultry and dairy collectives are significantly improving rural income streams and food security. These findings underscore the importance of gender-sensitive approaches in livelihood promotion. Despite these opportunities, gaps remain in the form of inadequate veterinary services, poor fodder availability, irrigation constraints, and weak storage and transport systems (Jha et al., 2012). Dependence on local traders and middlemen continues to reduce farmer profitability. However, integrated livelihood models that combine crops, livestock, and forest-based activities are increasingly recognized as a pathway to sustainable rural development. Evidence from the Agriculture Production Cluster (APC) model in Odisha and Jharkhand shows that collectivization, value chain integration, and technology adoption can improve income stability, enhance resilience, and build long-term livelihood security (OLM, 2018; PRADAN, 2020).

OBJECTIVES:

The primary objective of this study was to design and evaluate a sustainable livelihood framework capable of enhancing the annual income of small and marginal farming households in Katoria block of Banka district, Bihar. Anchored within PRADAN’s Agriculture Production Cluster (APC) model, the research aimed to examine the feasibility of integrating agriculture with livestock and allied activities to promote diversification, resilience, and inclusive growth.

To assess the income-expenditure dynamics of major livelihood activities, including crop cultivation, goat rearing, and backyard poultry, by engaging with 82 households across six villages, with 50 progressive farmers selected for detailed analysis. A further objective was to evaluate the availability and management of fodder resources and to explore the introduction of improved practices, such as Napier grass cultivation, to strengthen livestock-based livelihoods.

To identify and profile potential women agri-entrepreneurs within the APC framework, recognizing their role in household and community-level enterprises, and to explore institutional and policy support that could foster their development. In addition, the feasibility of establishing community-managed stock centers was examined to enhance farmers’ access to quality inputs and services. Ultimately, the internship sought to generate actionable insights for strengthening APC-based livelihood models and contribute to the discourse on sustainable rural development.

METHODOLOGY

This study adopted a mixed-method approach, combining both primary field-based data collection and secondary research to ensure a comprehensive understanding of livelihood patterns and opportunities in the selected region. The methodology was designed to capture household-level realities, validate them through participatory engagement, and situate findings within the broader discourse on rural development.

Study Area and Sampling:

The research was conducted in six villages of Katiyari Panchayat in Katoria block, Banka district, Bihar, namely Inaravaran, Lilavaran, Letwa, Sikatvaran, Uparchakmadia, and Giddhmarwa. These villages were purposively selected in consultation with PRADAN professionals, as they represent diverse livelihood practices under the Agriculture Production Cluster (APC) model. A total of 82 households were surveyed, out of which 50 progressive farmers were identified using stratified sampling for in-depth analysis.

Primary Data Collection:

Field surveys were undertaken using structured questionnaires to collect quantitative data on landholding size, cropping patterns, income and expenditure from agriculture, livestock, and poultry, as well as fodder availability and management practices. In addition, semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) were organized to capture qualitative insights into household livelihood strategies, challenges, and aspirations. Particular attention was given to women farmers and potential agri-entrepreneurs to understand gender-specific dynamics. Direct field observations, informal interactions, and transect walks were also employed to validate responses and strengthen contextual understanding.

Secondary Data Collection:

Secondary information was sourced from PRADAN’s internal documents, project reports, and training manuals. Institutional reports from NABARD, NDDB, and Odisha Livelihoods Mission on APC models provided comparative insights. Relevant government schemes, statistical reports, and published academic literature on smallholder farming systems, livestock development, and rural livelihoods were also reviewed. These secondary materials complemented the primary data and framed the study within established theoretical and policy perspectives.

ANALYSIS:

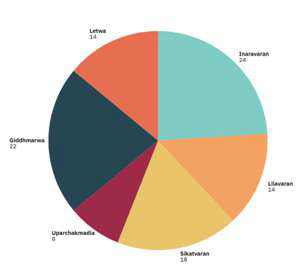

1. Distribution of Farmers of different villages in Katiyari Panchayat, Bihar

The pie chart presents the distribution of farmers from six different villages, based on the data collected during the internship.

Highest Contribution -Inaravaran (24%):

Inaravaran accounts for the largest share of farmers surveyed. This suggests a relatively higher engagement or accessibility in this village during the data collection process.

Giddhmarwa (22%) and Sikatvaran (18%):

These two villages also contributed significantly to the dataset, indicating good participation and possibly larger or more organized farming communities.

Moderate Participation -Lilavaran and Letwa (14% each):

These villages had a balanced representation, contributing equally to the survey. It could be due to logistical ease, village size, or farming population.

Lowest Representation – Uparchakmadia (8%):

This village had the least number of farmers surveyed. This might reflect smaller population size, accessibility issues, or lower farmer participation.

Insights for Field Work:

Data Skew: While the distribution is fairly balanced, Inaravaran and Giddhmarwa together account for nearly half the data. Interpretation of findings should factor in this skew.

Focus Areas: Villages with lower representation, like Uparchakmadia, might require more outreach or targeted engagement in future studies to ensure inclusivity.

Follow-up Planning:

The data suggests where future resources or interventions (like training or program rollouts) could be piloted, especially in high-participation villages like Inaravaran.

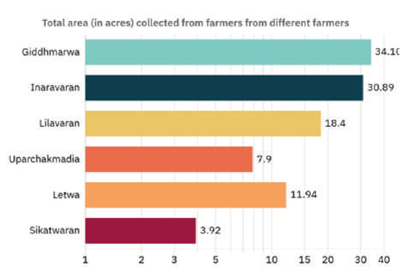

This bar graph represents the total agricultural land (in acres) reported by farmers from six different villages. The values show the sum of individual land holdings surveyed in each village.

Village-wise Interpretation:

Giddhmarwa – 34.102 acres

- Highest total landholding among all villages.

- Indicates a large number of farmers owning significant land or a few farmers with large holdings.

- Suggests high agricultural potential or focus.

- Inaravaran – 30.89 acres Second highest landholding.

- Despite a slightly lower total than Giddhmarwa, it still represents a major share of cultivable land.

- Inaravaran also had the most farmers surveyed (12) implying average landholding per farmer is around 2.57 acres.

Lilavaran – 18.4 acres

- Mid-range landholding.

- With 7 farmers surveyed, the average land per farmer is Approx 2.63acres, slightly higher than Inaravaran.

- Letwa 11.94 acres

- Lower than Lilavaran and Inaravaran but still a moderate total.

- Also had 7 farmers, averaging Approx1.71 acres per farmer, indicating smaller holdings.

Uparchakmadia – 7.9 acres

- One of the lower totals.

- With 4 farmers, average land per farmer is about 1.98 acres.

- Might reflect a mix of medium and marginal landholders.

- Sikatvaran – 3.92 acres Lowest total land area among the villages.

- Yet, 9 farmers were surveyed resulting in an average of just Approx 0.44 acres per farmer.

- This highlights a predominance of marginal farmers with very small landholdings.

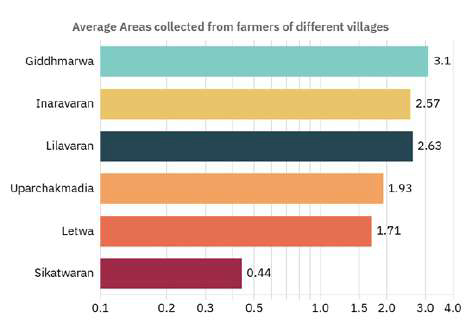

Average areas (in acres) collected from farmers of different villages:

This bar graph presents the average landholding per farmer in six villages, calculated by dividing the total land from each village by the number of farmers surveyed there. It helps to understand the scale of individual land ownership, which is crucial for designing interventions.

Village-wise Interpretation:

Giddhmarwa – 3.1 acres (highest):

- Farmers here own the largest average landholding.

- This suggests potential for commercial-scale agriculture or diversification into high-value crops.

- Indicates better land access, making it a good target for productivity-enhancing interventions.

- Lilavaran 2.63 acres

- Slightly above average landholding per farmer.

- These farmers could manage multi-crop farming or combine livestock and horticulture effectively.

- Scope for expanding sustainable practices like crop rotation or organic farming.

Inaravaran – 2.57 acres:

- Very close to Lilavaran, indicating moderate land access.

- Farmers here could benefit from efficient land-use strategies, like intercropping or introducing off-season vegetables.

Uparchakmadia – 1.98 acres:

- Below 2 acres on average.

- These farmers may face moderate land constraints, requiring a balanced mix of agriculture and allied activities (e.g., goat rearing).

Letwa 1.71 acres:

- Smaller landholding than Uparchakmadia.

- Interventions should prioritize crop planning, input optimizationand possibly SHG-based collectivization to improve economies of scale.

Sikatvaran – 0.44 acres (lowest):

- This is a critical finding the average farmer owns less than half an acre.

- Indicates severe land fragmentation and marginal farming conditions.

- Suggests livelihood diversification is essential here like backyard poultry, goat rearing, or wage-based programs.

- Government schemes or NGO support should focus on landless/marginal farmer development.

Insights & Implications:

- There is a clear disparity in average landholding ranging from 0.44 acres to 3.1 acres.

- Villages like Giddhmarwa, Lilavaranand Inaravaran have relatively better land access and could adopt resource-intensive or high-return practices.

- Sikatvaran and Letwa, with smaller average holdings, are better suited for low-investment, high-return livelihoods and community-based support systems.

- These insights are vital for tailoring interventions ensuring that each village receives context-specific development support.

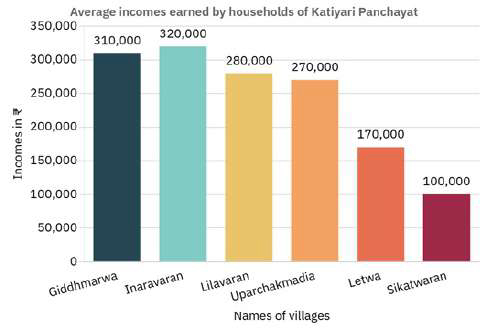

4. Average Income by households of Katiyari Panchayat:

The graph represents the average annual household income (in) from six villages under Katiyari Panchayat. This data provides insights into the economic well-being and livelihood performance in each village

Village-wise Analysis:

Inaravaran – 320,000 (highest):

- This village records the highest average income.

- The high income aligns with earlier data: large total landholding (30.89 acres) and moderate average land per household (2.57 acres).

- Indicates successful agricultural output or access to diversified income sources like remittances, livestock, or local businesses.

Giddhmarwa – 310,000:

- Slightly below Inaravaran.

- Notable because Giddhmarwa had highest total land area (34.102 acres) and highest average landholding per farmer (3.1 acres).

- Suggests that the land is being effectively monetized, possibly through cash crops or livestock-based income.

Lilavaran – 280,000:

- Third highest income level.

- With an average landholding of 2.63 acres, Lilavaran households seem to be making good use of their resources.

- Reflects a well-performing agrarian economy, possibly aided by local employment or support programs.

Uparchakmadia – 270,000:

- Surprisingly high income despite only 1.98 acres per household on average.

- Suggests income diversification, e.g., migration income, wage labour, or microenterprise activity.

- This is a key village to explore non-farm income strategies.

Letwa – 170,000:

- Income drops notably here.

- With 1.71 acres average landholding, the returns appear lower, possibly due to low productivity or lack of market access.

- May benefit from focused intervention in agricultural techniques or infrastructure support.

Sikatvaran – 100,000 (lowest):

- This village has both the lowest income and lowest land access (0.44 acres per household).

- Highlights severe economic marginalization.

- Indicates urgent need for livelihood diversification, such as goat rearing, backyard poultry, wage-based schemes (MGNREGA), or group-based farming.

Key Insights:

- Income correlates positively with landholding, but not perfectly. For example, Uparchakmadia performs better than Letwa despite having only slightly more land.

- Sikatvaran is economically vulnerable, needing special attention from development programs.

- Giddhmarwa and Inaravaran can be seen as growth hubs, suitable for pilots and scaling interventions.

- Variation in income suggests a mix of livelihood strategies beyond just agriculture e.g., wage labor, remittances, or allied activities.

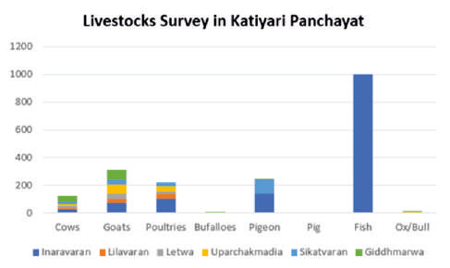

Livestock’s survey in Katiyari Panchayat:

The chart represents the livestock diversity and distribution across six villages in Katiyari Panchayat. It includes different types of livestock such as cows, goats, poultry, buffaloes, pigeons, pigs, fish and ox/bull.The stacked bars show how each village contributes to the total count for each livestock category.

Category-Wise Interpretation:

1. Cows:

- Present in all villages, with small contributions from each.

- Giddhmarwa and Inaravaran show relatively higher numbers.

- Indicates cows are a common livestock asset in the region.

2. Goats:

- Goats are widely distributed.

- All six villages contribute significantly.

- Uparchakmadia, Giddhmarwa and Inaravaran have a notable presence.

- Suggests that goat rearing is a key livelihood activity, especially for smallholders.

3. Poultries:

- Also widely distributed across villages.

- Inaravaran and Giddhmarwa have the highest shares.

- Backyard poultry is likely a low-cost, high-benefit enterprise for marginal farmers.

4. Buffaloes:

- Very low numbers, with a tiny contribution from Giddhmarwa only

- Shows buffalo rearing is rare and possibly declining in this region.

5. Pigeons:

- Moderate presence, mostly from Inaravaran.

- This is done for preparing Humusfrom their dung rearing, not necessarily for commercial purposes.

6. Pigs:

- Very limited presence, not visible in most villages.

- Could be culturally sensitive or less preferred.

7. Fish:

- Dominant category by far, with nearly 1000 fish entries entirely from Inaravaran.

- Indicates the presence of a significant fish farming activity in Inaravaran.

- Fish may be pond-based, suggesting access to water resources.

- It stands out as a potential enterprise model for replication.

8. Ox/Bull:

- Present in very small numbers, scattered lightly across villages.

- Likely used for agricultural purposes, but mechanization or declining use is suggested by low numbers.

Village-Wise Insights:

Inaravaran: Most diversified in livestock, especially strong in fish, poultry and goats.

Lilavaran: Moderate presence in common livestock like goats and poultry.

Giddhmarwa: Contributes across many types, second strongest in livestock after Inaravaran.

Uparchakmadia: Focused mostly on goats and poultry.

Letwa & Sikatvaran: Have minimal but present livestock holdings; goats and poultry dominate.

Implications for Livelihood Planning:

- Fish farming in Inaravaran is a high-potential enterprise and can be promoted in nearby villages with water access.

- Goat and poultry rearing are the most accessible options for smallholders and women-led SHGs.

- Diversification gaps in buffalo, pig and ox/bull suggest potential for targeted support if culturally accepted.

- Villages like Letwa and Sikatvaran may benefit from livestock expansion programs, especially backyard poultry or goat units.

MODEL DESIGN

Income model for livelihood model for marginal farmers landholding: 0 to 90 decimal combining goat rearing, poultry, vegetable cultivation and staple crops, targeting an annual income 2.5 Lakhs within 2-3 years. This integrated approach emphasizes asset enhancement, income diversification and sustainable farming practices.

SRI Training-System of Root Intensification (SRI) training is provided to farmers to enhance paddy cultivation practices. This method emphasizes the use of fewer seeds, reduced water, and organic inputs to achieve higher yields. The training imparts techniques such as transplanting young seedlings, maintaining wider spacing, practicing intermittent irrigation, and adopting mechanical weeding-ultimately improving both productivity and sustainability.

| Components | Current status | Proposed Intervention (2-3 years) | Area | Annual Income Expected | Support Needed |

| Goats | 5 mothers goats, income ₹40000/year | 10 breeding Goats | Shed based | ₹80000-₹90000 | Shed support, vet care, fodder, buck access, stall feeding |

| Poultry | 10 birds, income ₹40000/year | 50-60 (Desi) Egg sale | Backyard | ₹60000-₹70000 | Feed training, Low-cost feeding, market linkage |

| Poultry | Paddy, Maize, Wheat for consumption and sale | High-yield variety, direct sowing, organic inputs | Approx 40 Dismal | ₹15000-₹20000 | Irrigation, seed support, SRI Training |

| Vegetables | Few crops in limited area | Potato, Chilli, Tomato, Brinjal (2-3/ cycles) | Approx 40 Dismal | ₹50000-₹60000 | Nursery, IPM training, mulching, marketing |

IPM Training-Integrated Pest Management (IPM) training teaches farmers to control pests using eco-friendly methods like natural predators, crop rotation and traps. Chemicals are used only when necessary. This approach reduces environmental harm, protects beneficial insects, lowers costs and helps farmers make informed, sustainable decisions to safeguard crop health effectively.

Proposed Intervention-It refers to the set of planned actions, strategies and support systems that are suggested to improve the income, productivityand resilience of rural farmersespecially smallholdersthrough targeted activities in agriculture, livestockand allied sectors.

Key components of Proposed Intervention Integrated Farming System Approach:

romote a combination of stable crops, vegetables, goat rearing and poultry. Ensure year-round income from diversified sources.

Capacity Building:

- Provide technical training on crop management, animal health, feed practicesand poultry care.

- Organize exposure visits and handholding support through field functionaries or NGOs.

Irrigation Infrastructure & Input Support:

- Promote low-cost irrigation solutions (e.g., drip/sprinklers/pumps) for 9-10 month water availability.

- Supply quality inputs: seeds, chicks, goat vaccines, feed and organic manure.

Formation & Strengthening of Producer Groups (PGs):

- Mobilize small/marginal farmers into PGs for collective production and aggregation.

- Enable linkages with banks, markets and service providers.

Livestock & Poultry Promotion:

- Strengthen backyard poultry and small ruminants through vaccination, breed improvement and stall feeding.

- Promote low-cost housing, feed kits and community health support.

Vegetable Cultivation Intensification:

- Use even small land parcels for high-value vegetable crops.

- Promote staggered sowing for continuous harvest and cash flow.

Post-Harvest & Marketing Linkages:

- Support with grading, packing, cold storage (if feasible) and transport.

- Facilitate direct market linkage with farm gate buyers, FPOs, or institutional buyers.

Financial Inclusion:

- Facilitate access to credit through SHGs or KCC (Kisan Credit Card).

- Promote saving and reinvestment habits.

Goal of Intervention:

To enable a small/marginal farmer with limited landıolding (e.g., 0-90 decimal) to generate a stable income of 2.5 lakh per annum within 2-3 years, through:

- Diversification

- Aggregation

- Improved practices

- Strong market linkages

Expense and Income Chart:

| Components | Expenses | Income |

| Goats | ₹8000 | ₹80000-₹90000 |

| Poultry | ₹7000 | ₹60000-₹70000 |

| Crops | ₹5000-₹7000 | ₹15000-₹20000 |

| Vegetables | ₹25000-₹35000 | ₹50000-₹60000 |

| Total | ₹45000-₹55000 | ₹205000-₹240000 |

Assumption behind the livelihood model:

| Goat rearing | • Average 1.5 kidding/year per goat with 2 kids per kidding • 80% kid survival rate • Sale price ₹3,500-₹4,000 per kid (6-8 months old) • Fodder available on farm or nearby • Deworming and vaccination dose |

| Poultry (Egg layer) | • Improved/desi breeds used • 180-200 eggs/year/bird • Death < 10% yearly • Average egg sale price ₹7-10 • Local demands for eggs and live birds |

| Crops | • Land under staple is approximate 50 Dismal • Improved variety used • Use of family labor • Irrigation availability for 9-10 months • Minimal hired labor cost 50%-60% produce sold |

| Vegetable | • 2-3 crop cycles possible due to irrigation • Yield Approx 60-80 quintal/year across crop • Average selling price ₹6-10/kg (Depends on crop and season) • Local market access within 10-15km • Family labor used primarily |

| Irrigation | • Source is available for 9-10 months (well/stream/pump) • Covers >70% of cropped area |

| Family labor | • Family members are available and involved full-time or part-time • Labor requirement for livestock and vegetable farming is manageable |

| Institutional Support | • Farmer is a member of SHG or VO and has access to small credit (₹10,000-₹25,000) • Convergence with schemes like MGNREGA (for shed, irrigation), Livestock Dept. (for chicks, vet), Agri Dept. (for seeds, nursery) |

| Market conditions | • Stable or growing demand for vegetables, eggs and small livestock • Farmer has access to at least weekly market (hatiya) or local buyers |

| Farmer motivation and training | • Willingness to adopt • Training/exposure supported by NGOs or Governments • Gradual adoption of practices over 2-3 years |

Landless farmers, though lacking cultivable land, can build sustainable livelihoods through livestock-based activities, particularly goat rearing and backyard poultry. These require minimal space, low investment and offer regular income. Goat rearing, with 5-6 breeding does, can be scaled up to 8-10 goats. Each doe can produce 3-4 kids annually and the sale of kids at 6-8 months can earn ₹60,000-₹90,000 per year. Key requirements include access to breeding bucks, vaccination, fodderand basic housing support (e.g., through MGNREGA or government schemes). Similarly, backyard poultry, especially with improved breeds like Vanaraja, offers ₹50,000-₹70,000 annually from egg and bird sales. Women and youth can easily manage this activity. In addition, landless households often engage in wage labor or SHG-based enterprises. With access to credit, training and market linkages, such households can earn ₹1.5-2.2 lakh annually, with potential to reach *2.5 lakh over time through government convergence and collective action.

Livelihood model for farmers owning 100-200 dismal of land, who are engaged in goat rearing, backyard poultryand crop cultivation. With mostly year-round irrigation available and existing income from livestock, this farmer can scale and diversify activities to achieve a target annual income of 2.5 lakh within the next 2-3 years.

| Component | Current status | Proposed scaling | Est Annual income By year 3 |

| Goat rearing | 5 mother goats; income approx. ₹40000 | Expand to 8-10 does, better breed buck, stall feeding, vet care, fodder plot | ₹280,000-₹290,000 |

| Poultry | 10 birds income Approx. ₹240,000 | Scale to 40-60 birds (Desi breed) regular vaccination, feed management, partial meat sale | ₹260,000-₹270,000 |

| Crops | Small area under paddy/maize/wheat | Cultivate 50 Dismal to 100 Dismal with improved varieties, SRI method, partial market sale | ₹15.000-₹20.000 |

| Vegetable | Some land under vegetables | 50 Dismal-100 Dismal; 2-3 seasonal crops/year, nursery, mulching, market linkage | ₹60,000-₹80,000 |

| Fodder + Composting | Not practiced/limited | 5-10 dismal for fodder (Napier): goat/poultry manure compost used in vegetables | ₹210,000-₹215.000 (cost-saving) |

| Other (SHG/NREGA etc.) | Not included directly | SHG-linked income (e.g.. sewing, knitting, tailoring) or wage/entitlements | ₹10,000-₹15,000 (optional) |

Expense and Income Chart:

| Components | Expenses | Income |

| Goat rearing | ₹10000-₹12000 | ₹80000-₹90000 |

| Poultry (Eggs + Birds) | ₹10000-₹15000 | ₹60000-₹270000 |

| Vegetable | ₹10000-₹15000 | ₹15000-₹20000 |

| Staple Crops | ₹240000-₹260000 | ₹60000-₹280000 |

| Fodder + Compost Savings | ₹5000 | ₹10000-₹15000 |

| SHG/Other Income (optional) | ₹25000 | ₹10000-₹15000 |

| Total | ₹80000-₹112000 | ₹235000-₹290000 |

Source; Survey 2025

Assumption behind the livelihood model:

| Components | Assumptions |

| Goat rearing | • Initial herd size: 5 goats; scaled to 8-10 breeding does • Each doe produces 3-4 kids/year • Kid survival rate: Approx. 80% • Basic shed available (MGNREGA support) • Fodder partly grown on-farm or locally procured |

| Poultry | • Scaled from 10 to 40-60 desi breed birds • Each bird lays Approx. 180-200 eggs/year • Egg sale price: ₹7-10 • Death kept below 10% with timely vaccination • Poultry shed space available or created using SHG funds |

| Crops | • 50-100 Dismal used for paddy/wheat/maize • Mostly for consumption; 20-30% marketed • Improved seeds and family labor used • Low cash investment, irrigation available |

| Vegetables | • 50-100 Dismal under tomato, brinjal, chili, etc. 2-3 cropping cycles/year • Average yield: 60-80 quintals/year • Local market price: ₹6-10/kg • Inputs: nursery, mulching, compost, drip/surface irrigation |

| Irrigation | • Assured water availability for 9-10 months • Access via handpump, well, or community source • Sufficient for year-round cropping |

| Fodder & Compost | • 5-10 dismal area for Napier cultivation • Goat/poultry manure composted • Compost replaces chemical fertilizers for vegetables • Saves ₹10,000-15,000 yearly in input costs |

| SHG/Wage income | • Member of SHG or VO • Access to loans for poultry/goat shed • Occasional wage work (e.g., MGNREGA, local labor) • Other microenterprises (sewing, knitting, tailoring) possible |

Source: Based on the Survey 2025

This model is realistic and scalable for a smallholder farmer with 100-200 dismal land, especially inareas with reliable irrigation and strong SHG/VO presence. It reduces dependency on a single income source, uses family labor effectively and aligns with schemes supporting livestock, irrigation and women’s entrepreneurship.

Livelihood model designed for a farmer owning approximately 250 decimals of cultivableland, already engaged in goat rearing and backyard poultry, with access to irrigation for most of the year. The objective is to help this farmer generate an annual income of 2.5 lakh within the next 2-3 years through optimal integration of livestock and agrilcture.

Income Expanse Chart:

| Components | Expenses | Income |

| Goat Rearing | ₹10,000 | ₹80,000-₹90,000 |

| Poultry | ₹7000 | ₹60,000-₹70,000 |

| Crops | ₹18000 | ₹20,000-₹25,000 |

| Vegetable | ₹35000 | ₹70,000-₹80,000 |

| Fodder & Compost | ₹5000 | ₹10,000-₹15,000 |

| SHG/Microenterprise/Wage | ₹5000 | ₹10,000-₹15,000 |

| Total | ₹80000 | ₹250000-₹295000 |

Assumptions behind the livelihood model

| Components | Assumptions |

| Goat rearing | 10 breeding does; each produces 3-4 kids/year with 80% survival; ₹3,500-₹4,000/kid sale price |

| Poultry | 50-70 birds; 180-200 eggs/year per bird; ₹7-₹10/egg; some birds sold live for meat |

| Crops | Paddy, wheat, maize; 1-1.25 acres; improved seeds and SRI/line sowing; partial market sale |

| Vegetable Irrigation | Tomato, chili, Potato, brinjal etc. on 1.25-1.5 acres; yield ₹60-₹80 quintal/year; local sale at ₹6-₹10/kg |

| Fodder & Composting | Available for 9-10 months; electric pump or community irrigation.10-15 dismal under Napier grass; compost used in vegetable plots reducing fertilizer cost |

| SHG/Wage Income | SHG membership provides access to credit and microenterprise; wage income through MGNREGA |

With 250 dismal land, irrigation access and existing engagement in goat and poultry, the farmer is well positioned to scale operations into a resilient, multi-income livelihood. By strategically expanding livestock units and optimizing land through mixed cropping and vegetable intensification, the farmer can achieve 2.5 lakh/year within 2-3 years.

CONCLUSION:

Internship involved extensive fieldwork across villages such as Inaravaran, Lilavaran, Letwa, Sikatvaran, Uparchakmadia and Giddhmarwa. Conducted surveys on agriculture and livestock, capturing data on cropping patterns, landholding sizes and livestock varieties including goats, poultry, cattle and occasional fish. Documented Tasar cultivation practices and assessed adoption of fodder innovations like Napier grass and Azolla. Observed high rates of seasonal migration among landless and smallholder farmers due to limited income opportunities. Studied non-farm livelihood trends, especially among women, including tailoring and knitting. Evaluated Self-Help Groups (SHGs) in multiple hamlets to understand their outreach and the extent of women’s access to mobile phones, healthcare and ration shops.Gained practical exposure to rural development, strengthened field research skills and developed a deeper understanding of sustainable and inclusive livelihood promotion. The designed livelihood model is feasible and well-suited to small and marginal farmers with landholdings ranging from landless to 250 Dismal. The integration of goat rearing, backyard poultryand diversified crop cultivation ensures income stability and resource optimization. Availability of irrigation for most months, convergence with government schemes, SHG support and market linkages enhance the model’s practicality. The approach is cost-effective, scalable and capable of generating an annual income of ₹250000 within 2-3 years, making it a sustainable strategy for rural livelihoods. Further research can explore the long-term impact of integrated livestockcrop models on household income stability, food security and women’s economic participation. Comparative studies between different landholding categories can help refine component prioritization. There is also scope to assess market accessibility, value chain linkagesand climate resilience of the model. Piloting digital tools for farm planning, livestock health tracking and price forecasting may offer new insights for scaling and replication.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

1. Integrated Farming Systems: Farmers should be encouraged to adopt integrated models combining crops, livestock, and allied activities such as goat rearing, backyard poultry, and tasar silk cultivation. This diversification reduces income risks, improves nutritional security, and ensures a more stable cash flow across seasons. Demonstration plots and pilot initiatives may be undertaken to showcase successful models.

2. Strengthening Fodder Availability: Given the current scarcity of quality fodder, systematic promotion of green fodder crops like Napier grass and Azolla cultivation is recommended. Village-level fodder banks could be established to support farmers during lean periods, reducing dependence on free grazing and paddy straw.

3. Women-Centric Livelihood Promotion: Women should be recognized as central actors in livestock and micro-enterprises. Targeted capacity-building programs, access to credit through SHGs, and the identification of women agri-entrepreneurs can help institutionalize gender-inclusive growth. Linking these women with producer collectives and government schemes will further enhance their agency.

4. Community-Based Service Infrastructure: Establishment of community-managed stock centers under the leadership of agri-entrepreneurs would ensure timely access to quality inputs, veterinary medicines, and technical services. These centers could function on a cost-recovery basis, generating local employment while reducing dependence on external suppliers.

5. Market Linkages and Value Addition: Strengthening Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) and building direct linkages with wholesale buyers, processors, and cooperatives will help eliminate exploitative intermediaries. Additionally, small-scale value addition units for poultry, dairy, and tasar silk should be promoted to enhance profitability at the village level.

6. Capacity Building and Extension: Continuous training in sustainable agricultural practices such as System of Root Intensification (SRI), Integrated Pest Management (IPM), and scientific goat and poultry rearing is essential. Exposure visits and regular engagement with subject-matter specialists will ensure knowledge dissemination and adoption of innovations.

7. Policy Convergence and Institutional Support: Finally, convergence with government schemes like NRLM, ATMA, and RashtriyaKrishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY) should be leveraged to channel resources and subsidies into APC clusters. Partnerships with technical institutions and NGOs can further provide the necessary ecosystem for scaling livelihood interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT:

I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. K. Ravichandran, IFS, Director, IIFM Bhopal,, DrAnandHindolia, Chairperson SI, for fostering such a supportive academic environment that encourages field-based learning. Author’s Sincerely acknowledges PRADAN, Katoria, Bihar, for granting the invaluable opportunity to undertake Summer Internship and gain first-hand exposure to the complexities of rural livelihoods. I am especially indebted to my reporting officer, Mr. Saroj Kumar, whose constant guidance, constructive feedback, and encouragement enriched my learning experience. I extend my heartfelt thanks to Mrs. Muniya Murmu, my field guide, for her unwavering support, patience, and for sharing her local knowledge, which helped me connect meaningfully with the community. I am also grateful to Mr. Rajesh Parida for his insights on livestock and gender-related aspects, and to Dr. Anil Yadav, Veterinary Doctor, for his valuable technical guidance on animal health and fodder management. I would also like to acknowledge my faculty guide, Dr. S. P. Singh, for his academic mentoring and critical inputs, and the Summer Internship Chairperson for smooth coordination. Special thanks are due to the PRADAN team, SHG members, and community participants, whose cooperation and openness made this study possible. Finally, I remain indebted to my family, peers, and friends for their motivation and encouragement throughout this journey.

REFERENCES

Birthal, P. S., Joshi, P. K., & Gulati, A. (2007)

Diversification in Indian agriculture: Trends, determinants, and implications for smallholders. Agricultural Economics Research Review, 20(2), 237-257.

Choudhury, B. N., & Jena, S. (2011)

Tasar sericulture in tribal livelihoods: A case from Jharkhand and Bihar. Journal of Rural Development, 30(2), 199-214.

Jha, A. K., Singh, K. M., &Meena, M. S. (2012)

Constraints of rainfed agriculture in Eastern India and livelihood opportunities. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 12(1), 1-5.

PRADAN (2025).

Professional Assistance for Development Action.

Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India (2006).

The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006.

National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) (2020).

Model Bankable Project on Goat Farming.

Ram Kishan Singh, & Bindra Devi (2021).

“Backyard Poultry Farming as an Income-Generating Activity in Rural India.” Indian Journal of Animal Sciences, 91(6), 481-487.

HDFC Bank Parivartan (2022).

CSR Collaboration with PRADAN – Promoting Livelihood Clusters in Bihar and Jharkhand.

Directorate of Animal Husbandry, Bihar (2021).

Livestock Development Initiatives in Banka District

Manohar Lal Das & Thakur Das (2019).

“Livelihood Diversification through Tasar Sericulture in Jharkhand and Bihar.” Journal of Rural Development, 38(2), 232-246.

Authors:

1. Associate Professor- Environment and Developmental Economics, Indian Institute of Forest Management, Nehru Nagar Bhopal

2. PFM student 24-26 batch, Indian Institute of Forest Management, Nehru Nagar Bhopal