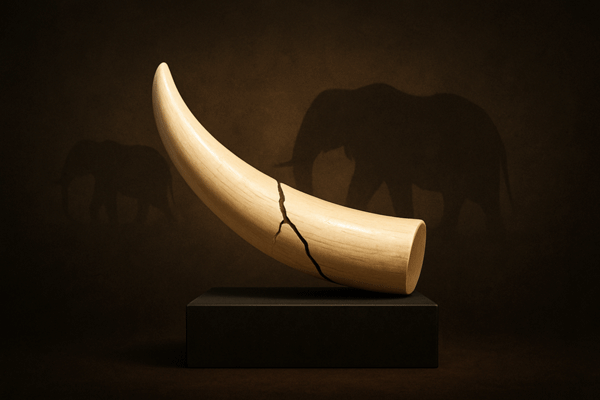

The ivory illusion: How Mohanlal’s trophies exposed the cracks in India’s wildlife law

When Kerala’s biggest movie icon found himself in the dock over elephant tusks, the case turned into a parable of power, privilege, and the perils of procedural shortcuts in India’s conservation regime

It began as a routine Income Tax raid in 2011. When officials entered Malayalam superstar Mohanlal’s home in Kochi’s Thevara neighbourhood, they expected financial documents, perhaps some unaccounted cash. Instead, what they found were four gleaming elephant tusks and 13 intricately carved ivory artefacts displayed like heirlooms.

The officers seized them immediately under the Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972, which strictly prohibits possession of ivory without government certification. The recovery made headlines across Kerala, a state that reveres its elephants as temple deities and cultural symbols. Yet, over time, the case slipped into silence, overtaken by the actor’s continuing fame and the bureaucracy’s quiet accommodations.

Fourteen years later, on 25 October 2025, the Kerala High Court finally brought the issue back into sharp focus. A Division Bench declared that the ownership certificates and government orders that had legalised Mohanlal’s possession of ivory were “illegal, void and unenforceable.” With that judgment, the court punctured the illusion that procedural leniency could paper over the law.

The decision did not merely expose a celebrity’s brush with wildlife law; it laid bare a deeper crisis — the selective enforcement of conservation statutes, the erosion of procedural integrity, and the moral confusion of a society that worships elephants but tolerates ivory.

From seizure to certification: How a case lost its teeth

The 2011 seizure set off what initially appeared to be a straightforward prosecution. The Forest Department registered a case in the Judicial First Class Magistrate Court, Perumbavoor, charging Mohanlal under the Wild Life (Protection) Act.

The actor’s explanation was simple: the tusks came from a captive elephant that had died of natural causes, and he had merely preserved them as memorabilia. He claimed he was unaware that possession without prior declaration violated the law.

For a few years, the case remained in procedural limbo. Then, in 2015, the Kerala government issued a notification under Section 40(4) of the Act, inviting declarations from individuals possessing ivory or other animal articles, with the promise of ownership certificates under Section 42.

This legal window effectively allowed those already in possession of ivory to “regularise” it retroactively. Mohanlal submitted his declaration. The Chief Wildlife Warden verified the claim and granted him an ownership certificate for two pairs of tusks and thirteen artefacts.

The certificate changed everything. The ivory was no longer contraband; it was now “lawfully owned property.” The State then moved to withdraw the criminal prosecution. What had begun as an offence had quietly transformed into a matter of paperwork.