HIMALAYAN FORESTS UNDER PRESSURE: UNDERSTANDING DRIVERS OF DEGRADATION AND PATHWAYS TO RECOVERY

Anshu Kumari, Priyanshu Bishan, Anita Tomar and S.C. Arya

The Himalayan ecosystem, covering approximately 12.84% of India’s total geographical area (Negi, 2009), is one of the world’s most biologically diverse and ecologically significant regions. Recognized as a global biodiversity hotspot, it harbors more than 8,000 species of flowering plants, nearly one-fourth of which are endemic (Singh & Hajra, 1996). Among these, around 10% are trees, 8% wild edibles, and over 15% medicinal plants (Rawat & Chandra, 2014), reflecting the immense ecological, cultural, and economic importance of this mountain realm. The community structure and species composition of Himalayan forests are shaped by a delicate interplay of environmental and human factors such as altitude, slope, rainfall, temperature, and disturbance intensity (Lomolino, 2001; Luth et al., 2011). These forests are inherently dynamic, constantly adapting to shifting climatic conditions and varying degrees of human pressure. Their structure and regeneration patterns reveal much about the resilience and vulnerability of these ecosystems. However, this priceless biological wealth now faces escalating threats from natural and anthropogenic disturbances, leading to habitat degradation and biodiversity loss.

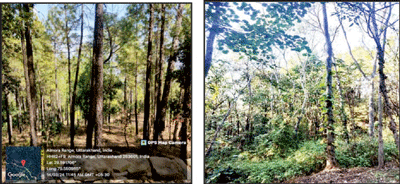

The forests of Himalaya are primarily composed of Himalayan Chir pine Forest-9/C1b, Oak Forest-12/C1a, Himalayan Mixed Coniferous Forest-12/C1d (According to Champion & Seth classification, 1968). ThePinus roxburghii (chir pine) dominates the pine woods, which are often found on sun-exposed slopes between 1,000 and 1,800 meters above sea level. These woods are prone to fire and frequently have deteriorated understories as a result of grazing, resin tapping, and litter collection. Oak forests, which are primarily made up of Quercus leucotrichophora (banj oak), are essential for conserving soil and water and grow well at higher elevations (1,500-2,400 m). They support rich biodiversity and sustain perennial springs but are declining due to lopping and conversion to pine. The mixed forests, which include species like Rhododendron arboreum, Myrica esculenta, and Lyonia ovalifolia, create a transition between pine and oak zones. These forests contribute significantly to the ecological stability of the mid-Himalayan region and show a high degree of structural variety (Fig1,2,3).

Fig 1-Himalayan Chir pine Forest Fig 2-Himalayan Mixed Forest Fig 3- Oak Forest

DRIVERS OF FOREST DEGRADATION

Forest Fires- It is a cause of degradation mostly in pine-dominated forest as pine needles and resin content make it more flammable. Fire season in India is at peak from March to May. Fires, whether they are started intentionally to encourage grazing or accidentally or seasonally, can destroy seedlings and understory plants (Fig-3). The normal regeneration pattern is altered by frequent fires because they change the characteristics of the soil, lower organic carbon, and promote invasive or fire-tolerant species. Despite being less vulnerable to fire, oak and mixed woods can still have fires, particularly during dry summer that are made worse by climate change.

Fig 3- Forest Fires in Chir pine Forest

Invasive Alien Plant Species– A major threat to all types of forests is the growth of invasive alien plant species like Parthenium hysterophorus, Ageratinaadenophora, and Lantana camara etc. These species often colonize open and disturbed areas, where they establish quickly and outcompete native vegetation for light, nutrients, and water. Their rapid growth alters the forest structure, suppresses natural regeneration, and makes habitats less suitable for native flora and fauna. By spreading faster than other species, invasive species can dominate large areas, significantly change the ecosystem and reduce biodiversity (Fig-4).

Overgrazing by Livestock-

The livestock (cow, goat, sheep) moves freely in forest which feeds the tender shoots of seedling and makes regeneration of the forest poor by leaving the adult species to dominate. Livestock further compact the soil by stepping on it, which inhibits root development and water infiltration. In addition to reducing tree density over time, grazing encourages the spread of exotic plants and undesirable species, changing the forest’s composition (Fig-5)

Lopping and Felling- Branches of Pine, Oaktrees are often lopped for fuelwood and firewood collection, which reduces tree crowns, leaf area for photosynthesis, and lowers reproductive potential (fewer flowers and fruits). As the tree canopy is open, it makes favorable conditions for unwanted species to grow. The removal of leaf litter from the forest floor also depletes soil organic matter, lowering fertility and moisture retention. Excessive fuelwood extraction in pine forests compromises the health of the forest by exposing the soil and understory to erosion (Fig-6)

Overharvesting of NTFP- Unsustainable harvesting of Non timber forest products (medicinal plants, wild edibles) such as Rhododendron arboreum, Myrica esculenta (Fig-7) removes biomass and seed resources which reduces seed bank and regeneration capacity. Disturbance of soil when roots, tubers, or rhizomes are dug out and loss of understory diversity.

Forest Fragmentation- The factor contributing to the loss of forests is encroachment and land conversion for infrastructure, communities, and agriculture. To create roads or terraced fields, forest portions are frequently cut down, causing soil disturbance and ecosystem fragmentation. This kind of fragmentation makes tree populations more vulnerable to invading species and natural disasters like landslides, decreases genetic exchange, and isolates tree populations.

Conclusion

From pine and oak to a variety of mixed varieties, Himalayan forests are essential for preserving biodiversity, controlling the temperature, conserving soil and water, and sustaining the way of life for millions of mountain inhabitants. However, in addition to natural and climate-related disturbances, human-induced pressures like overgrazing, lopping, fuelwood collecting, land conversion, and the introduction of exotic species are posing an increasing threat to these forests. These pressures decrease species diversity, change the structure of forests, and interfere with natural regeneration. It is crucial to put into practice efficient management techniques in view of India’s forest policy, which promotes keeping 33% of the nation’s geographical area covered by forests. Forest resilience can be increased through actions including invasive species management, natural regeneration, degraded area restoration, lowering human stresses, and community engagement. By adopting integrated and sustainable approaches, Himalayan forests can expand and recover, ensuring ecological stability and continued provision of essential ecosystem services for future generations.

References

Lomolino, M.V. 2001. Elevation gradients of species-density: historical and prospective views. Glob EcolBiogeogr., 10: 3-13 Luth, C., Tasser, E., Niedrist, G., Dalla, Via J. and Tappeiner, U. 2011. Plant communities of mountain grasslands in a broad cross-section of the Eastern Alps. Flora, 206: 433-443. Negi, S.P. 2009. Forest cover in Indian Himalayan states-An overview. Indi. J. For., 32: 1-5.

Rawat, V.S. and Chandra, J. 2014. Vegetational Diversity Analysis across Different Habitats in Garhwal Himalaya Singh, D.K. and Hajra, P.K. 1996. Floristic diversity. In: Gujral, G.S. and Sharma, V. (eds.). In: changing perspectives of Biodiversity Status in the Himalaya. British Council, New Delhi. pp 23-38.

Author is

1 ICFRE Ecorehabilitation Centre, Prayagraj, India

2 G.B.Pant National Institute of Himalayan Environment, Almora, India

3 ICFRE Ecorehabilitation Centre, Prayagraj, India

4 G.B.Pant National Institute of Himalayan Environment, Almora, India