EXCERPTS FROM “THE HIGHLANDS OF CENTRAL INDIA”

(by Capt. J. Forsyth)

Capt. J. Forsyth of the Bengal Lancers ‘discovered’ Pachmarhi in 1857. He revisited the place at the instance of the Chief Commissioner in 1862 and started construction of a house later called “Bison Lodge” which became the Headquarters of the Forest Department and remained so till 1927.

INTRODUCTION:

In 1861 were constituted what have since been known as the Central Provinces, under the Chief Commissionership of the late Sir Richard Temple. One of the first steps taken was the organisation of a Forest Department.

My design, is to present, in a more popular and accessible form, the lighter and more picturesque aspects of a country in which an increasingly large section of our countrymen take as interest. The culturable wastes were becoming much in demand by enterprising settlers. The forest question also became urgent, timber being required in large quantities by the railways, while a fear arose of the impending exhaustion of the whole forests of the country.

Ecology – The region is remarkable as forming the meeting ground of some forms of vegetable and animal life, which seem to be characteristic of North-eastern and South-western India. The principal forest tree of upper India is the Sal (Shorea robusta), a tree whose habit it is to occupy, where it grows at all, the whole area, almost to the exclusion of others.

To the west of this the characteristic and most valuable forest tree is the Teak (Tectona grandis). The Teak tree is, not so exclusive in its habit of growth as the Sal, appearing rather in the form of scattered clumps among other forms than as the sole occupant of large areas. I believe that the Sal, where the soil is suitable has exterminated the Teak. Where the Teak does not meet with this rival, it flourishes. Within the Sal region, in the hills immediately to the east of the town of Mandla, there is a considerable area covered by Teak, to the total exclusion of the Sal. The whole of this region is composed of a trap overflow; and all around it, as soon as the gigantic and lateritic formations recommence, the Sal again entirely abolishes the Teak. Again, within the area of the trap and Teak, in the valley of the Denwa river, 150 miles west of the farthest limit of the general Sal region, is found a solitary isolated patch of the latter, here the Sal grows on a sandstone formation. It is not then a very violent assumption to suppose that the Sal forest at one time extended down the Narbada vally as far as the Denwa, and that, when the country was cleared, this little patch alone was left securely nestled under the cliffs of the Mahadeo range. Equally with Sal tree, several prominent members of the Central Indian Fauna belong peculiarly to the north eastern parts of India. These are the Wild Buffalo (Bubalus ami), the twelve-tined “swamp” deer (Rucervus duvaucellii), and the red jungle-fowl (Gallus ferruginous). All these are plentiful within the area of the great Sal belt, but do not occur to the west of it, excepting in the Sal patch of the Denwa valley. Two other large representatives of the eastern and western faunas, the wild elephant and the Asiatic lion, also appear to have formerly extended far into this region. The former in the time of Akbar, ranged as far west as Asirgarh, but is now confined to the extreme east of the province. A lion was killed in the Sagar district in 1851, and another a few year ago only a few miles from the Jabalpur and Allahabad railway. The hog-deer (Axis porcinis) I have never met with in the west of the province, nor it is very numerous even in the east, though very common in the Sal tracts of Northern India. I indicate another matter in connection with this subject. A tribe called Korkus, closely connected with what is called the Kolarian stock, which is represented by the Kols and Santals of Bengal, is found embedded among the Gonds of these central hills. Thus we have an outlier of the human tribes of Eastern India existing along with an outlier of its vegetable and animal forms. It is a most singular coincidence.

PAGHMARHI REVISITED (1862) TRAVELLING KIT:

In my shooting excursions I had always marched with only a single small tent, about eight feet square. It affords room enough for a light folding bedstead of bamboo, a cane stool, a small folding table, a brass basin and stand, and your portmanteau and guns, which is all the furnishing that the mere sportsman or explorer should require. All this, with a good supply of such eatables and drinkables as are not to be had in the wilderness, will go on a good camel. I added another tent twelve feet square, for the servants and a few newly entertained native foresters who were to assist in may explorations. To carry these additional impediments I had four or five of the rough little unshod and unkempt country ponies, called tottoos. On the 11th of January I bade adieu to the pretty little station of Jabalpur.

CLIMATE:

The climate of Central India in the cold season, that is, from November to March, is almost perfect for the life of combined outdoor exercise and indoor occupation which forms the healthiest sort of existence in India. Nothing can, in my opinion, exceed the exhilarating effect of a March at such a season, with pleasant companions through a country teeming with interest in its scenery, its people and its natural productions, such as is this region of the Narbada valley.

WILDLIFE:

Snipes and wild fowl begin to arrive in these central regions of India, voyaging from the frozen wilds of Central Asia, early. in October, and before the end of November, every piece of water and swampy hollow affords its contingent to the guns.

Of larger game, the principal animal met with in the settled parts is the Black antelope. Not even in Africa, the land of antelopes, is there any species which surpasses the “black buck” in loveliness or grace. I have seen herds in the Sagar country, immediately after the Mutiny of 1857, when they were little molested, which must have numbered a thousand or more individuals. The Chinkara or Indian gazelle is another antelope very common in Central India. Considerably smaller than the black antelope, the gazelle also differs much from it in habits. It prefers low jungle to the open plain and trusts more to its watchfulness and activity than to speed. The antelope met with in the open country is the Nilgai. The old sites of deserted villages and cultivation, unfortunately so common, which are usually covered with long grass and a low bushy growth of Palas and Jujube trees, are seldom without a herd of nilgai.

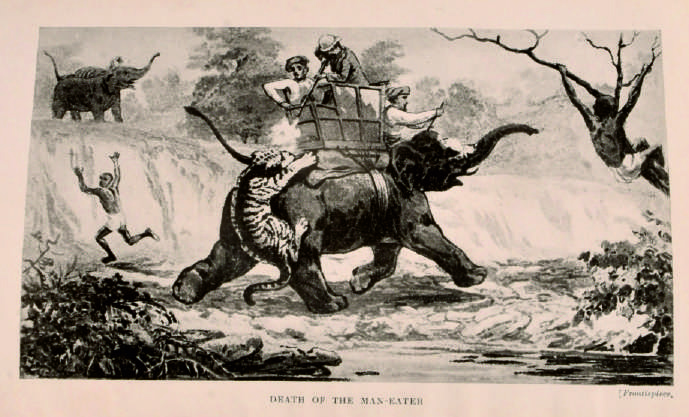

As, however, in a state of nature, there never are herbivorous creatures without their attendant carnivora to form a check and counterbalance to them, so we find various natural enemies attendant on the herds of antelope and nilgai, whose acquaintance the sportsman will occasionally make. The nilgai is a favourite prey of the tiger and the panther. Chief carnivorous creatures of the open country are the hunting leopard, the wolf and the jackal.

I have several times come across and shot the hunting leopard (cheetah) when after an antelope; but they cannot be called common in this part of India. They are of a retiring and inoffensive disposition, never coming near dwellings, or attacking domesticated animals, like the leopard or panther.

The wolf is extremely common in the northern parts of the province. They unite in parties of five or six to hunt, and the loss of human life from those hideous brutes has recently been ascertained to be so great that a heavy reward is now offered for their destruction.

Though not generally venturing beyond children of ten or twelve years old, yet, when confirmed in the habit of man-eating, they do not hesitate to attack, at an advantage, full-grown women and even adult men. The attack was commonly made by a pair of wolves, one of which seized the victim by the neck from behind, preventing outcry, while the other coming swiftly up, tore out the entrails in front. “The mighty boar” is found almost everywhere in the low jungle on the edge of cultivation, and sometimes in the sugar-cane and other tall crops, and with a liberal expenditure otself and horse may be ridden and speared in a good many places. On the 25th of January I quitted the main road down the valley, near the little civil station of Narsingpur, and struck off nearly at right angles to the South, marching direct to the hills that bounded the horizen in that direction.

I encamped at the end of this march at a place called Mohani, the scene of the works of the “Nerbudda Coal and Iron company”. Near Mohpani is one of the best snipe Jheels in the Province.

My next march lay under the northern-face of the main range of the Satpuras, which here form a bluff headland rising some 500 ft. above the plain, crowned by an old fortress called Chauragarh.

From my camp at Chaolpani a single peak of the Puchmuree hills was visible. It had not a very imposing appearance, however, as I find it recorded as “like half an egg sticking out of an immence egg cup”. A couple of bears came close up to the camp at night and commenced to fight, making a fearful noise. I halted a day at Jhilpa, the last village on the plains to make arrangements for the ascent and to procure guides, and on 22nd packed my small tent and a few necessaries on a pony, and with two attendants started up the hill on foot. When an elevation of 2000 feet had been attained the character of the scenery began to change.

After scrambling thus along the sides and bottoms of ravines for some miles, steadily rising at the same time we suddenly emerged through a narrow pass, and from under the spreading aisle of a large banyan tree (from which this pass gets its name of the Barghat) on to an open glade, covered with short green grass, and studded with magnificent trees which I found was the commencement of the plateau of Puchmurree. The village of Puchmurree was still distant and we hurried along over the almost level plateau to get shelter as soon as possible as we had already walked about seventeen miles and the sun was almost set.

Immense trees of the dark green harra (Terminalia chebula), the arboreous Jamun (Eugenia jambolana) and the common mango dotted the plain in fine clumps, and altogether the aspect of the plateau was much more that of a fine English Park than of any scene I had before come across in India. By and by, through the vistas of the trees, three great isolated peaks began to appear, glowing red and fiery in the setting sun against the purple background of the cloud bank. The centre one of the three, right ahead of us, was the peak of Mahadeo, deep in the bowels of which lies the shrine of the God himself, to the left, like the bastion of some giant’s hold rose the square and abrupt form of Chauradeo, while to the right and further off than the others, frowned the sheer scarp of Dhupgarh, the highest point of these Central Indian Highlands. The deep and gloomy dells that seam the Puchmurree block are the home of a splendid squirrel (Sciurus maximum), measuring two and half to three feet in length, and of a rich deep claret clour, with a blue metallic lustre on the upper parts of the body, the lower parts being rufous yellow. I spent many a long day in the chase of the bison on these splendid hills. I have frequently found both bison and sambaron the very top of Dhupgarh in the early morning.

Here I ascertained the existence of the Bara-Singha, ortwelve-tined deer (Rucervus duvaucellii), an animal which, like the Sal forest in which it lives, had been supposed not to extend to the west of the Sal belt in the Mandla district.

The panther is pretty common in Puchmurree.

Coursing foxes was another great amusement.

PUCHMURREE AGAIN:

On the 28th of May being seized with the preliminary symptoms of what turned out to be a severe attack of jungle fever, brought on by constant exposure to the hot sun by day and the malarious air of these close valleys by night I determined to return to the cool heights of Puchmurree, which I did by the Bori route, in four longish marches. I never enjoyed anything so much as when I bared my head to the cool breeze that swept over the Pachmurree plateau, as I topped its edge after climbing up the stiff ascent of the Ron Ghat. The theromometer in my tent below had been ranging from 98 degrees to 110 degrees during the heat of the day, and had once reached 120 degrees, when I went over and lay like a tiger under some jaman bushes by the waterside. In the verandah of the lodge on Puchmurree, which was now nearly finished, it stood at 86 degrees, while the nights which below had not for weeks been free from hot winds, were cool and delicious up here. The first rain of the monsoon fell on the 12th of June. The wild flowers too, again burst forth on all sides, under the influence of the gentle showers that now almost daily visited the hilk It was inexpressibly delighful to be up here, in a perfectly English climate, with cool gray skies, and greenery all about, after the terrible grilling we had suffered for two long months down below.

BISON LODGE, COMPLETED:

By great exertions we got the house roofed just in time to hang a bison’s frontlet over the door, and christen it “Bison Lodge.”

Since then the Forest Department has regularly occupied the lodge on the hill and laid out extensive gardens round about.

I left the plateau on the 28th of July to march to Jubblepur. It was a melancholy procession down the hill, that march of my fever stricken followers, crowded on the backs of the elephants that carried them in several trips to the carts that awaited them below.