UNDERSTANDING YIELD IN SAL FOREST OF MADHYA PRADESH AND CHHATTISGARH

Uttam Kumar Sharma, IFS, MP

Yield regulation the process of determining sustainable yield and prescribing methods for its realization-is central to scientific forest management. Its basis lies in the principle that the forest grows continuously across the entire area, but the annual yield is extracted only from a designated working area known as the “coupé.” Thus, while growth occurs everywhere, felling is spatially and temporally regulated. The timing, location, and method of felling are determined by the silvicultural system in practice.

For even-aged forests, Silviculture systems such as Clear Felling, Shelterwood, and Irregular Shelterwood are applied, while uneven-aged forests are generally managed through the Selection Silviculture system. In fact, silvicultural interventions can even convert uneven-aged forests into even-aged ones.

Yield regulation is firmly rooted in scientific principles, requiring both technical knowledge and long-term planning. To illustrate, I present results from the working plan data of Sal forests in Madhya Pradesh managed under the Selection-cum-Improvement (SCI) Working Circle.

A common perception in society including sometimes among foresters is that the Forest Department undertakes excessive felling under the guise of silvicultural operations, leading to forest degradation. However, working plan records tell a different story. The following data provide evidence of how yield regulation maintains sustainability in practice.

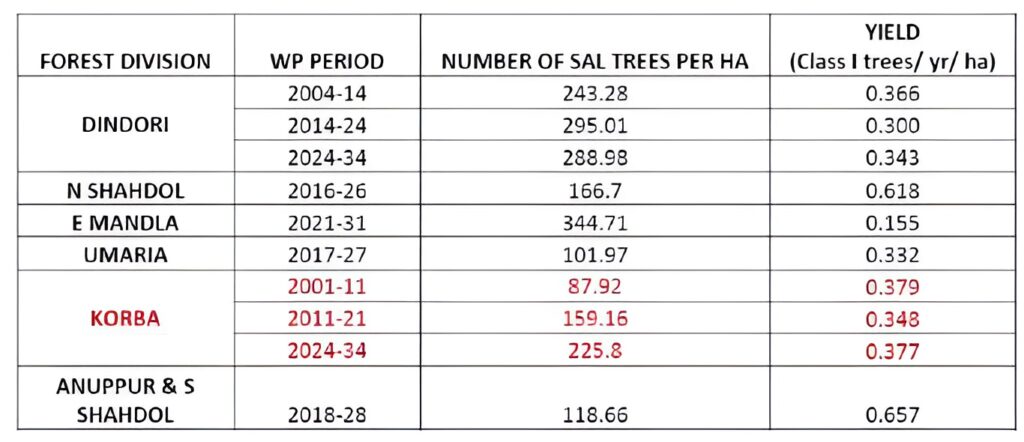

1. Following is the number of trees per ha of Sal in different Sal-bearing areas of MP and Korba division of Chhattisgarh (CG): E Mandla division has the highest number of Sal trees per ha (344.71 trees/ha). Highest number of Sal trees above selection girth is in N Shahdol division (33.2 trees/ha).

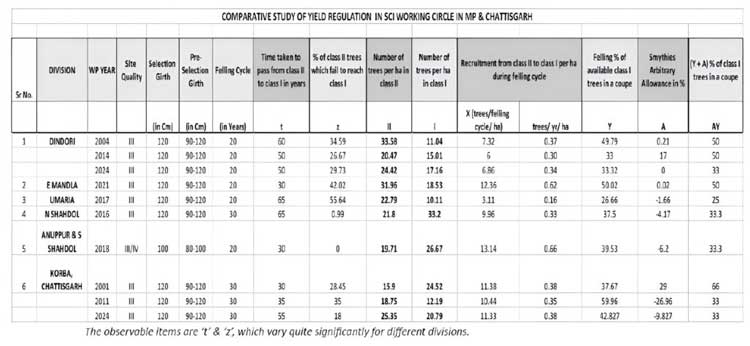

2. Based on the Working Plan data and prescriptions for SCI WC, following table shows the result of yield calculation using Symithies’ Safeguarding Formula:

In the context of yield regulation, the recruitment of Class II trees into Class I (denoted as ‘X’) represents the annual yield per hectare in a given division. Since felling cycles vary across divisions, comparison based on cycle length would be misleading. Therefore, recruitment has been standardized to trees per hectare per year, enabling fair comparison across divisions.

The analysis shows that recruitment is highest in Anuppur and South Shahdol (0.66 trees/ha/year), followed by East Mandla (0.62 trees/ha/year). The lowest recruitment is in Umaria (0.16 trees/ha/year), while in most other divisions it falls between 0.3-0.4 trees/ha/year.

In practical terms, this means that the permissible annual felling in each division corresponds to these recruitment rates. Thus, approximately 0.66 trees per hectare can be harvested annually in Anuppur and South Shahdol without compromising sustainability, while only 0.16 trees per hectare may be removed in Umaria. It should also be noted that the actual yield realized will be influenced by the value of parameter ‘A’: a positive value of A increases the yield proportionally, while a negative value reduces it.

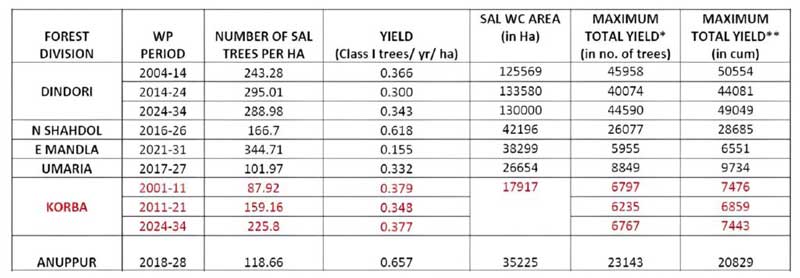

The calculation clearly demonstrates that the intensity of felling is extremely low. On average, more than 200 Sal trees are present per hectare, while the prescribed yield amounts to only a fraction of a single tree per hectare per year. For instance, in divisions with the highest recruitment, the figure is about 0.6 tree per hectare per year, against a standing stock of roughly 166 Sal trees per hectare. Placed in perspective, removing less than one tree annually from a hectare containing hundreds of Sal trees cannot reasonably be equated with “destruction of forests.” The scale is simply too small to have any adverse ecological impact. The following table shows the total yield of Sal trees during a year in the division:

*Total Yield calculated here is without using the value of ‘A’ in Smythies’ Safeguarding Formula.

**Taking volume of one selection Sal tree above >120 cm girth as 1.1 cum and above >100 cm girth as 0.9 cum.

Many people, when confronted with the large absolute figures of timber felled, instinctively conclude that such removals must be destructive and that our forests cannot withstand this level of felling pressure. However, the data tell a very different story. In reality, the removal amounts to only 0.3 to 0.6 trees per hectare per year, while the availability is about 200 Sal trees per hectare.

In other words, less than one tree is harvested annually from a hectare that holds hundreds of trees. Such a low intensity of felling is well within the regenerative capacity of the forest and does not threaten its sustainability. Why then does the perception persist that silvicultural felling is harming forests? Much of it arises from a limited understanding of yield regulation and the scientific safeguards built into working plans. Yield prescriptions are conservative by design, ensuring that harvest never exceeds natural growth and recruitment. In reality, the data reaffirm that silvicultural operations under the Selection-cum-Improvement Working Circle are sustainable, carefully regulated, and far from exploitative. What is needed, therefore, is greater public awareness-especially among those who focus only on the total number of trees felled-so that forest management is understood in the right context of scientific yield regulation.

Author is

An IFS Officer in M.P.