WESTERN GHAT IS IN STRESS

UMA SHANKER SINGH, IFS, DSc and PRAKRITI SRIVASTAVA, IFS

ORIGIN OF WESTERN GHATS:

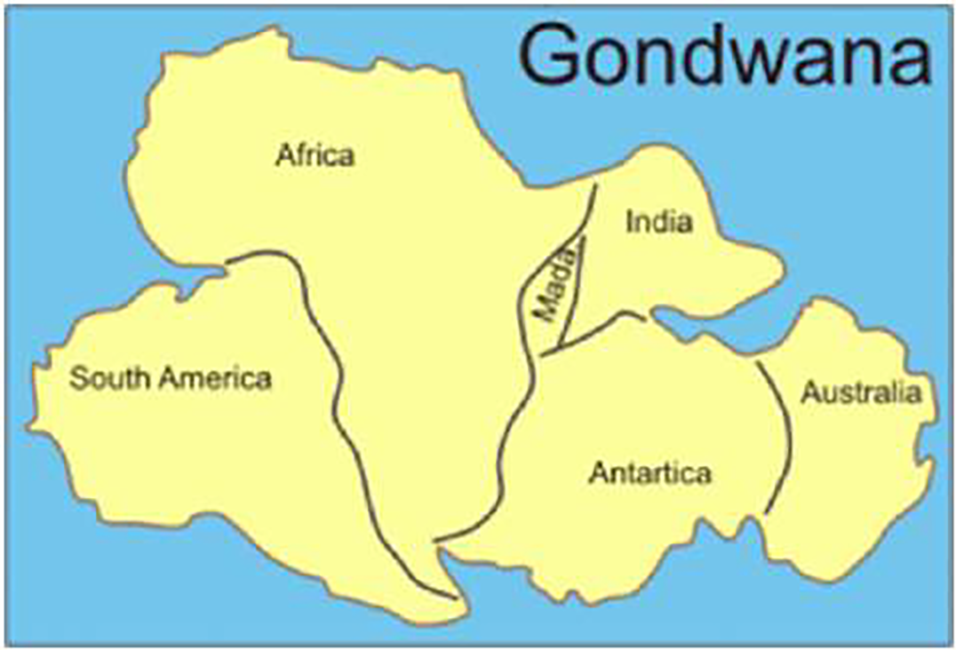

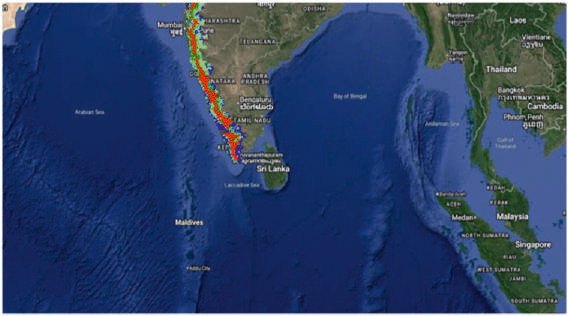

A chain of mountains running parallel to India’s western coast, approximately 30-50 km inland, the Ghats traverse the States of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Goa, Maharashtra and Gujarat. These mountains cover an area of around 140,000 km² in a 1,600 km long stretch that is interrupted only by the 30 km Palghat Gap at around 11°N. Older than the great Himalayan mountain chain, the Western Ghats of India are a geomorphic feature of immense global importance. It is one of the 36 hotspots of biological diversity in the world. States surrounding the range depends heavily on western Ghats for irrigation, agricultural purposes, and tourism. The western Ghats are older than the mighty Himalayas. It is formed after millions of years of chaos. They are considered as the mountainous faulted and eroded edge of the Deccan Plateau. Geologic evidence indicates that they were formed during the break-up of the supercontinent of Gondwana some 150 million years ago. Gondwana has consisted of modern South America, Africa, Madagascar, India, Australia and Antarctica.

When the Gondwana break-up happened, the Indian plate detached and travelled towards the Eurasian plate. There is a theory that the west coast of India came into being somewhere around 100 to 80 million years ago after it broke away from Madagascar. After the break-up, the western coast of India would have appeared as an abrupt cliff some 1,000 metres in height. Soon after detachment, Indian plate drifted over Reunion hotspot, a volcanic hotspot in the earth’s lithosphere near the present-day location of Reunion (21°06’S, 55°31′E). It moved up in this drift and the heat beneath the generated basaltic magma rose upward causing uplift by crustal arching. This geological event that took place about 120-130 million years ago gave rise to the Western Ghats and the Indian plate was inclined in an easterly direction. Afterwards, a series of volcanic eruptions for million years gave rise to the extensive Deccan Traps and thereby moulded the Northern Western Ghats to a large extent. Since the Western Ghats are the result of upliftment the underlying rocks are ancient. In some parts of Nilgiris, we could find ancient rocks as a piece of evidence for this. These ancient rocks are 200 million years old.

A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF WESTERN GHAT:

The Western Ghat is called “a treasure trove of biodiversity” and “the water tower of Peninsular India”. It is one of the global ‘hotspots’ of biodiversity. It consists of a wide variety of forest types such as tropical wet evergreen, montane stunted evergreen (shola), moist deciduous, dry deciduous and dry thorn forests, and grasslands. Some of these are critical habitats for plants and animals. The landscape is the headwaters of all major peninsular rivers in India, ensuring water security for the region. The Western Ghats is also critical for as many as 58 major Indian rivers that originate from it, including Godavari, Krishna, Cauvery, Kali, Bedthi, and Sharavati.The Western Ghats landscape is dominated by forests. The total area under the Western Ghats is about 1,29,037 sq. km, out of which about 87,307 sq. km is under forests.According to the Forest Survey of India, area under forests in the Western Ghats is increasing marginally in recent years. But this includes increase in area under plantations such as coffee, coconut, areca, cashew, cocoa and mango which are included in the definition of forests.A study in the southern region, comprising the states of Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, showed that between the period 1920 and 1990, about 40 per cent of the original vegetation cover was lost or converted to another form of land use.western Ghat is very important in terms of its biodiversity. Nearly 4000 species of flowering plants or about 27% of country’s total species are found in Western Ghat. It is home to many endemic species of flowering plants including medicinal plants, endemic fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals and invertebrates. The Western Ghats is a megadiverse region that is home to the largest wild population of Bengal Tigers and the Asian elephants in India, in addition to being home to thousands of other rare and endemic species of flora and fauna. The Western Ghats, therefore is not only important for India but also holds immense value for the world, due to which it has been recognised as a UNESCO heritage site. The Western Ghats are also home to millions of people, many of whom still reside inside forests and protected areas. It is estimated that presently there are 10,976 households present inside Protected Areas (PAs) of the Western Ghats in the states of Karnataka, Kerala (Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary), and Tamil Nadu (Mudumalai and Sathyamanglam Tiger Reserve).

WESTERN GHAT IS UNDER DEFFRENT STAGES OF DEGRADATION:

Land use changes in the Western Ghats over the last century caused by agricultural expansion, conversion to plantations and infrastructural projects have resulted in loss of forests and grasslands. While land use change remains the major threat to Western Ghats biodiversity, the intensive harvesting of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) such as fuel-wood, bark, leaves, fruits, exudates, etc., has also contributed to loss of biodiversity and forest cover. NTFP extraction con tributes significantly to local household income in tropical regions and has been viewed as preferable to con version to other land uses when it is sustainable. However, non-sustainable resource extraction can have deleterious consequences for biodiversity and affect the livelihoods of the users. The spatiotemporal analyses of land use show that Western Ghats, which is among 36 global biodiversity hotspots, saw a loss of 5% evergreen forest cover with an increase of 4.5% built-up cover, and 9% agriculture area. Fragmentation analyses also highlight that interior forest constitutes only 25% of the forest landmass, depicting the fragmentation pressure, impacting local ecology. A study on ecological fragility has revealed that 63,148 km2 area under very higher ecological fragility, 27,646 km2 under high ecological fragility, 48,490 km2 as moderate and 20,716 km2 as low ecological fragility.

Threats:

Much of the original forests of the Western Ghats still persist, but they are highly fragmented, and under tremendous threat of both outright conversion and further fragmentation. These threats emanate from illegal habitat conversion by anthropogenic activities like livestock grazing, forest fires, collection of non-timber forest products and illegal logging, encroachments as well as poaching. Construction activities for infrastructure development in the form of roads, dams, mining activities also are a major threats. The region witnessed large-scale land cover changes during the past century due to unplanned developmental activities with industrialisation and globalisation. This necessitates implementing mitigation measures involving stakeholders to address the impacts through location-specific conservation measures. Framing conservation and sustainable developmental policies entail delineation of ecologically sensitive regions by integrating bio-geo-climatic, ecological, and social factors representing dynamics of socio-ecological systems, impacts, and drivers.

LOSS OF FOREST IN WESTERN GHAT:

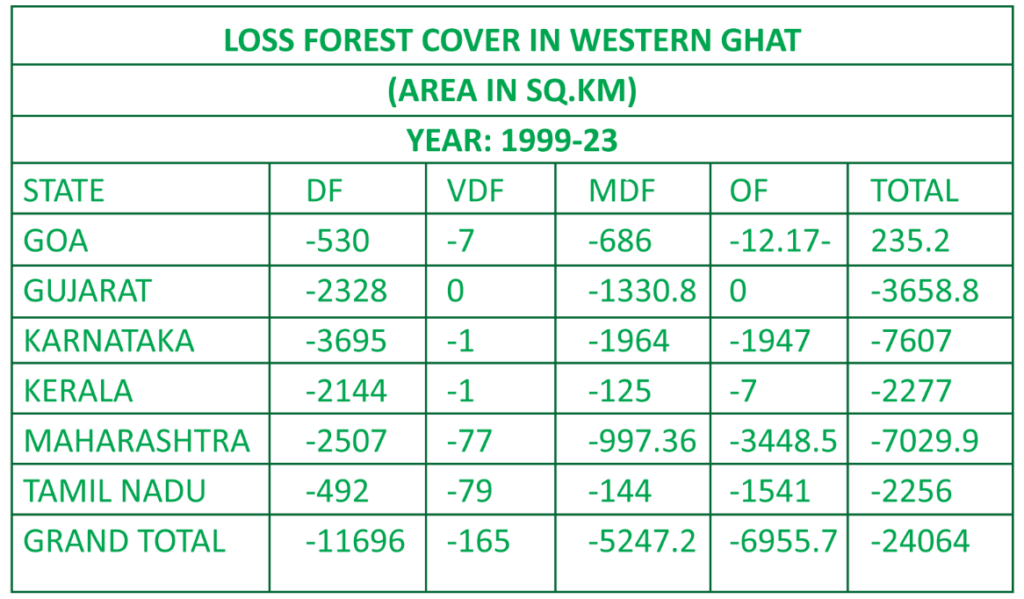

A study on the deforestation in the Western Ghats show that the estimated changes in forest cover between 1973 and 1995 in the southern part of the Western Ghats using satellite data. The study area of approximately 40,000 km2 showed a loss of 25.6% in forest cover over 22 years. The dense forest was reduced by 19.5% and open forest decreased by 33.2%. As a consequence, degraded forest increased by 26.64%. There has been a great deal of spatial variability in the pattern of forest loss and land use change throughout the region. Our estimates of deforestation in the region for the contemporary period are the highest reported so far. In yet another study it tells a different story. In this study the deforestation was quantified over a period of past nine decades. The classified forest cover maps for 1920, 1975, 1985, 1995, 2005 and 2013 indicates 95,446 (73.1%), 63,123 (48.4%), 62,286 (47.7%), 61,551 (47.2%), 61,511 (47.1%) and 61,511 km2 (47.1%) of the forest area, respectively. The rates of deforestation have been analysed in different time phases, i.e., 1920-1975, 1975-1985, 1985-1995, 1995-2005 and 2005-2013. The grid cells of 1 km2 have been generated for time series analysis and describing spatial changes in forests. The net rate of deforestation was found to be 0.75 during 1920-1975, 0.13 during 1975-1985, 0.12 during 1985-1995 and 0.01 during 1995-2005. Overall forest loss in Western Ghats was estimated as 33,579 km2 (35.3% of the total forest) from 1920’s to 2013. Land use change analysis indicates highest transformation of forest to plantations, followed by agriculture and degradation to scrub. The dominant forest type is tropical semi-evergreen which comprises 21,678 km2 (35.2%) of the total forest area of Western Ghats, followed by wet evergreen forest (30.6%), moist deciduous forest (24.8%) and dry deciduous forest (8.1%) in 2013. Even though it has the highest population density among the hotspots, there is no quantifiable net rate of deforestation from 2005 to 2013 which indicates increased measures of to Global Forest Watch data (2017) says thatthe four districts of Karnataka lost 2,208 ha of forest area Dakshin Kannada district lost 955 ha, followed by Udupi (857 ha), Uttara Kannada (236 ha) and Kodagu (160 ha). Since 2001, the two districts namely, Dakshin Kannada and Udupi lost more than 70% of total trees coverage areas. These two districts account for 14,400 ha of tree cover loss out of a total of 20,000 ha. The report about the forest cover published in ISFR Table: 1Loss Forest Cover in Western Ghats between 1999-23 was studied in detail then it was found that between 1999 and 2023 Western Ghats lost 11861 square kilometres of very dense forest and 5247.2 of square kilometres MDF.

THE PRESENT CARBON STOCKS IN WESTERN GHATS:

As per a study carried out by Ramachandra and Bharath (2019), the forests of Western Ghats currently store a total of 1.23 MGg (million gigagrams or tetra metric Tt) of carbon in both above ground biomass as well as in soil, with a carbon sequestration potential of 0.81 MGg per year. In case of the biodiversity-rich primary forests in central and southern Western Ghats, the forests store 600 Gg/ha of carbon.

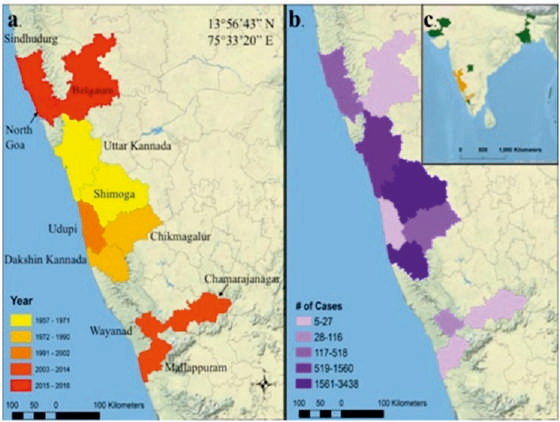

FOREST LOSS AND KYASANUR FOREST DISEASE: A DIRECT CONNECT

Over the past two decades, scientists have been alarmed by the rapid spread of an infectious disease transmitted by tick bites that afflict forest-dwellers in the verdant, biodiverse tropical forests of the Western Ghats running parallel to India’s west coast. Caused by a virus, Kyasanur Forest Disease, or ‘monkey fever’ as it is also known because it infects and sometimes kills monkeys too, sickens about 400 people in the region each year, although cases vary each year widely. A vaccine exists, but it is weak; new infections continue and a death reported was the year 2020. The disease was first identified in the state of Karnataka in 1957, but post-2000, scientists have been puzzled by its expansion northward to the states of Goa and Maharashtra and southward to Tamil Nadu and Kerala. And cases from the northern states have spiked in 2016 and 2017.

Cases of Kyasanur Forest disease in India depicted by (a) year of the first case in each district (n = 16), (b) number of human cases (n = 9594), and (c) and all seroprevalence antibodies discovered outside of this study’s region of interest (n = 6). Map and description from Chakraborty et al. 2019.

According to data released by Global Forest Watch in 2019, the rate of forest loss in the Western Ghats has intensified from 2012 to 2017. Many villagers have been displaced from their original lands into deforested areas, often at the periphery of new agricultural plantations. Scientists have long-suspected that forest loss might have played a role in the rise of Kyasanur Forest Disease (KFD). Now, a team of scientists has found concrete evidence for this association. Using models, a team of researchers examined the relationship between the landscape suitability of KFD and forest loss and mammalian species richness. They mapped the total outbreaks between 2012 and 2019 and gathered satellite data on forest loss. Their analysis found that an increase in both forest loss and mammalian species richness was associated with an increased risk of KFD outbreak. Generally speaking, forest loss reflects a more significant human presence in that landscape and deforestation can alter the composition of communities of populations in an ecosystem, which in turn can affect the way individuals of a species interact with each other and other species including humans.Curiously, another study published early in 2019, reported that in 1983-84, there was a massive outbreak of KFD with 2,589 cases. Coincidentally, they noted in a 1983 news article that 400 hectares of virgin forests in the Western Ghats were cleared around that time a huge amount compared to previous years to establish cashew plantations. Yet another study on the Impact of Plantation Induced Forest Degradation on the Outbreak of Emerging Infectious Diseases in Wayanad District by KakoliSaha, Kerala, based onGIS tools, remote sensing data, extensive field work and disease data to discover the relationship between the LULCC and disease outbreak. The study revealed that the emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) have increased recently due to forest degradation. The study was done in two parts. In the first part, land use and land cover change of the Wayanad district was analysed for the period of 1950 to 2018. The result of the analysis shows that a significant amount of forest has been converted into agricultural and forest plantations over the time. The second part involves understanding the impact of plantations on the outbreak of EIDs. It was found that cases of EIDs were high in those gram panchayats where forests were encroached by plantations.

RIVERS FLOWING FROM WESTERN GHATS:

The Western Ghats are a major watershed, with many rivers originating there. Specifically, there are 81 rivers that have their source in the Western Ghats. These rivers flow both east and west, with west-flowing rivers emptying into the Arabian Sea and east-flowing rivers eventually joining larger rivers like the Kaveri and Krishna. The west flowing rivers, such as the Periyar, Bharathappuzha, Netravati, Sharavathi, and Mandovi, have a shorter and faster flow due to the shorter distance and steeper slopes. The major east-flowing rivers are Godavari, Krishna, and Kaveri along with numerous smaller tributary rivers like the Tunga, Bhadra, Bhima, Malaprabha, Ghataprabha, Hemavathi, and Kabini.

WHY MOST OF THE RIVERS ARE DRYING UP?

In April 2024, two shocking news reports revealed that the upper reach of the Cauvery River at Dubare in Kodagu and its tributary, Hemavathi near Sakleshpur in Karnataka, had dried up. This unprecedented event has caused widespread concern, as the perennial rivers from the Western Ghats are the lifelines for farming and drinking water in both urban and rural areas. Several factors contributed to the drying of the Cauvery River, including global warming and El-Nino, which affect the SW monsoon rains in India.El-Nino, characterised by warm air from the central and eastern Pacific Ocean, disrupts SW monsoons, while La-Nina, characterised by cool air from the same region, tends to ensure better SW monsoon rains in India and droughts elsewhere in the world.Tree felling and an ineffective Forest Act have further degraded and shrunk the forests. Since the 1990s, invasive weeds such as Lantana, Parthenium, Senna spectabilis, etc, have further disrupted forest ecosystems, affecting natural regeneration. The remedies to tackle the catastrophic drying up of the Cauvery and other perennial rivers in the Western Ghats require committed effort from stakeholders and governments.

DAMS AND MINING ARE THREAT TO THE ECOSYSTEM:

Mini-hydro projects are still a major threat to Western Ghats, let us consider. Let us cite an example of a 24-MW hydro power project proposed for the Kumaradhara in Dakshina Kannada’s Puttur taluk has become a reality despite it is sanctioned on ‘private land’ prior to the Karnataka High Court order banning hydro projects. This hydel project could submerge 1,882 hectares of land, including agricultural fields and prime forests (Report commissioned by the Western Ghats Task Force in April) despite company claims that the project involves “no submergence of land, hence no loss of species or any resettlement or rehabilitation of the people. Cropland and plantations account for 36% of the land that could submerge while forests constitute 46%. The submergence of reserve forest areas (falling under Kunthur and Panaja range) have rare medicinal plants, endemic evergreen trees and endangered fish, and a perfect habitat for other animals. The other eye-opening example is 113 MW wind power project being developed near the Bhima Shankar Wildlife Sanctuary in Maharashtra. The Rs 772-crore project, spread over 14 villages and 194.66 hectares of reserve forestland, is promoted by Enercon (India) Limited.

The Gadgil report says that the project has caused substantial forest destruction and triggered large-scale soil erosion and landslides because of poor construction of roads on steep gradients. The construction rubble ends up on fertile farmland and in reservoirs of tributaries of the Krishna river. It says that the hills where wind mills have been installed receive high rainfall and are biodiversity-rich. The evergreen forest is contiguous with the Bhimashankar Wildlife Sanctuary, which is home to Maharashtra’s state animal, the Malabar Giant Squirrel or Ratufaindica. Reportedly, land rights of forest dwellers of the area have also not been settled. They are even being denied free movement in the area. Similarly, Illegal quarrying and mining are rampant in the Western Ghats. This despite the government’s claims that steps have been taken to check mining. We have seen as to what happened in Wayanad in the recent past. After the 2024 landslide in Wayanad, an analysis o satellite imagery revealed that the district housed at least 48 stone quarries, 15 of which were ocated in Environmentally Sensitive Areas (ESAS). These areas, identified in 2013 by a High-Level Working Group led by the space scientist Krishnaswamy Kasturirangan, are defined by having at least a fifth of their landscape under natural ecosystems, including biodiversity-rich zones, wildlife corridors, and heritage sites. Quarrying, mining, and other environmentally harmful activities are prohibited in ESAs to safeguard their ecological integrity but who cares?

FOREST LAND ENCROACHMENT IN WESTERN GHATS:

The Western Ghats, which covers about 60% of forest area of Karnataka, is recognized as one of the bio-diversity hotspots of the world. These forests are shrinking in recent years due to anthropogenic pressures, especially encroachment of lands for agriculture. It has led to forest fragmentation, loss of habitat and corridor for movement of wild animals, etc. A study carried out in the year 2014 on GIS based assessment of forest encroachment scenario over a period of three decades in Chikmagalur district of Karnataka revealed that the forest encroachment has considerably increased from 0.98% to 6.63% between 1975 and 2010 and the majority of encroachment has taken place during 1990 and 2000. Higher encroachments prevailed in moist and dry deciduous forest in the district. Another study carried out by G.R. Pramod Kumar in the year 2012 reveals that the encroachment in reserve forest of Kodgu districts accounts for 291.6 ha, 284.8 ha and 173.7 ha respectively for the year, 2010, 2000 and 1990.

COMMUNITIES LIVING WITHIN FORESTS:

Amongst the communities living inside the forests of the Western Ghats, there are a large number that feel isolated and marooned, especially from the younger generation who are eager to partake in the benefits of economic development, and desperately seek better lives and a good future for their children outside the protected areas. They seek better livelihood options, healthcare, education and access to basic facilities like electricity, public ration shops, etc. In addition to the lack of proper facilities inside the forests and the associated social issues, the forest-dwelling communities also live in constant threat of human-wildlife conflict. There are numerous examples where such forest-dwellers have lost their lives or have been gravely injured during incidences of human-wildlife conflict while carrying out simple, daily-life activities such as using toilets, collecting forest produce, etc. Often forest-dwelling communities continue to live in the forests facing huge adversity due to the lack of financial opportunities, education and awareness, as well as the fear of the unknown, even though they wish to go out and are desperate to seek a better life. They ultimately become a prisoner of their circumstances and continue living a sub-par live inside the forests often against their will. In their pursuit for better education for their children as well as to escape human-wildlife conflict, the forest-dwelling families take loans from money lenders, and become indebted for life. These circumstances limit their ability to exercise their democratic right to a better life.

CONCLUSION:

If the government would have paid a heed on Madhav Gadgil’s word on the western Ghats we would not have reached this stage of destruction but who hears the sane voice in today’s world? The report, headed by noted ecologist Madhav Gadgil, recommended that the government phase out mining projects, cancel damaging hydroelectric projects, and move toward organic agriculture in ecologically-sensitive sections of the Ghats. Recently dubbed a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Western Ghats is one of India’s largest wildernesses and home to thousands of species, many found no-where else. Many studies suggest that loss of remnant forest patches from these landscapes is likely to reduce biodiversity within Agro-ecosystems and exacerbate overall biodiversity loss across the Western Ghats. Conservation of these remnant forest patches through protection and restoration of habitat and connectivity to larger forest patches needs to be prioritized. In the densely populated Western Ghats, this can only be achieved by building partnerships with local land owners and stakeholders through innovative land-use policy and incentive schemes for conservation as well as attractive packages for voluntary relocation.Panchayats can play a pivotal role in conserving the environment while a committed political resolve and administrative support is essential.

Author Is:

Retd. IFS

Retd as PCCF UP

Presently working as

Director at Van Shakti

NGO H.Q. Lucknow

North India