The Himalayan Blunder

Introduction:

The Indian Himalayan Range (IHR), comprising 11 States and two Union Territories, had a decadal urban growth rate of more than 40% from 201 1 to 2021 .Towns have expanded, and more urban settlements are developing unsustainably. Almost all Himalayan towns, including State capitals, struggle with managing civic issues. For example, cities like Dehradun, Nainital, Srinagar, Guwahati, Shillong, and Shimla, as well as smaller towns, face significant challenges in managing sanitation, solid and liquid waste, and water. City governments are short of human resources by almost 75% and beset with rampant corruption. Cities continue to expand into the peripheries, encroaching on the commons of villages. Srinagar and Guwahati are examples of such expansion, leading to the plundering of open spaces, forest land, and watersheds. In Srinagar, land use changes between 2000 and 2020 showed a 75.58% increase. Water bodies have eroded by almost 25%, from 19.36 square kilometers to 14.44 square kilometers. These areas have been taken over by built-up real estate, increasing from 34.53 square kilometers to 60.63 square kilometers, a rise from 13.35% to 23.44% of the total municipal area. Nearly 90% of the liquid waste enters water bodies without treatment. Over the past few decades, tourism in the IHR has continued to expand and diversify, with an anticipated average annual growth rate of 7.9% from 2013 to 2023. Current tourism in the IHR often replaces eco-friendly infrastructure with inappropriate, unsightly, and dangerous constructions, poorly designed roads, and inadequate solid waste management, which leads to loss of natural resources damaging biodiversity and ecosystem services. The high costs of urban services and the lack of corridors place these towns in a unique financial situation. Current intergovernmental transfers from the center to urban local bodies constitute a mere 0.5% of GDP; this should be increased to at least 1 % of the GDP. Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh in the Himalayan region are extremely eco-sensitive, hundreds of people lose their lives due to landslides along with destruction worth crores of rupees. The h ill states are very vulnerable for example, the total area of 55,673 square kilometers of Himachal Pradesh, 38,249 sq. km area comes under high risk and 4,461 square km area comes under very high-risk area for landslides. The number of landslides has increased wildly on account of road construction in the hill states. More than 80 thousand trees have been cut for the highways in Himachal Pradesh and it has led to the reduction in carrying capacity of the area on account of the increasing construction in the tourism sector.A 1 15,000-megawatt power project has been planned in the Himalayan region, extending from Jammu and Kashmir to Arunachal Pradesh and for the restoration of the ecosystem all such plans needs to be dropped immediately. Due to the impact of these power projects, cracks have appeared in people’s houses, there has been an increase in natural calamities and water sources have dried up. Urni village in Kinnaur has been sinking continuously since 2009 and its cracks are increasing year by year and the village was hit by a landslide also in December 2022. Both Sikkim and Joshimath arc located in the eastern Himalayas and arc facing the same challenges and predicaments, Sikkim has been witnessing this hazard for the past one decade. Sikkim is also facing the problems in places like Dikchu, Shipgyer, Ramam in North Sikkim because of tunnels and the National Hydroelectric Power Corporation projects. The area is facing environmental disasters affecting the indigenous community of the region at large and loss of properties equally. Hydel projects, which commenced in the late 1990s in the state, can also be held accountable for the disasters, the expert said. They have affected the main Teesta river basin, where 90 per cent of Sikkim’s landmass is dependent hence, due to the construction of a bumper dam on Teesta river, people arc facing multiple land erosion in every part of Sikkim and also parts of Siliguri. Similarly, in Uttrakhand Himalayas some 7,000 MW of hydroelectric projects are either operating or being constructed in this fragile region; back to back; with no respect for the river or its need to flow naturally. The issue is not about hydropower generation or the need for energy or development. It is about the carrying capacity of this fragile region. which is even more 111 risk because of climate change. This needs to be assessed, bur by keeping the river first and our needs next. Otherwise, the river will continue to teach us bitter lessons; it will be the revenge and rage of nature. Humans will be shown as the puny things we are. Apart from the dams, numerous pharmaceutical companies and rampant unnecessary road widening, smart city projects and congested urban planning are putting more pressure on the ecologyleading to environmental disasters.

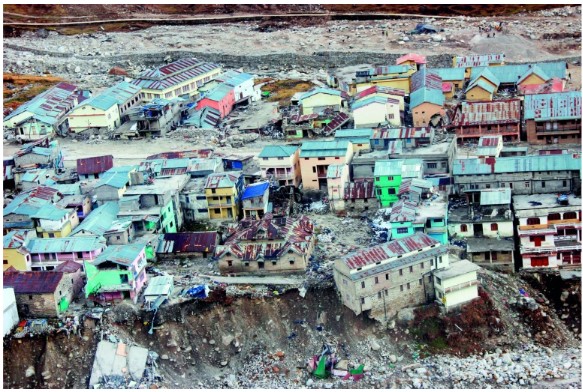

Joshimath is Sinking

Joshimath, a key transit point for tourists traveling to Badrinath and Hemkund Sahib, situated at an altitude of 1,890 metres from sea level in the Garhwal Himalayas, has a population of over 20,000. ft is located on the Rishikesh· Badrinath National Highway (NH-7) of Chamoli district which falls in Zone V of the Seismic Zonation map and almost sits on the tectonic fault line of Vaikrita Thrust (VT). What really made things worse is the weak foundation of the city. Sitting atop a glacial moraine, which are distinct ridges or mounds of debris that are laid down by a glacier, the town’s foundation has no solid rocks. These sediments have voids. making them extremely unstable. geologically. Spread over an area of 2,458 square kilometers, Joshimath is one of the six tehsils (blocks) in Uttarakhand’s Chamoli district. Previously, many incidents like landslides, subsidence or sinking and flash flood occurred in and around Joshimath city and multiple major and minor cracks also exposed on roads. walls und floors of houses. From 11 January 2023, major portion of Joshimath city started to sink continuously and major and minor cracks began to appear on roads, floors, ceilings and walls of houses. Around 1000 people have been evacuated from the unsafe area and risky buildings (Biswajit et al., 2023). The place was sitting atop with a disaster of this magnitude waiting to happen, but administration could not assess it. The Joshimath town is situated along a narrow gorge at the confluence of two major rivers: Dhauliganga and Alaknanda and is close to the Main Central Thrust (MCT) fault passing through on the southern side of town. So, it is prone to earthquake and also frequent rainfall. (YaspalSundriyal et al.,2023). The reactivation of these fault lines nearly 50-60 kilometers under the surface remains a big mystery. There are many contributory factors leading to the imbalance in the hill ecosystem but chiefly among them are the rapid rise in construction activities, widening of the Char Dham Yatra road and the National Highway 7, which runs through the town taking tourists and cargo to the holy shrine of Badrinath every year Joshimath’s problems with slope instability have given worse as a result of unplanned construction that didn’t take bearing capacity into account (USDMA. 2022). The widening of the road brought more and more hotels springing up in and around Joshimath therefore, religious tourism also spiked. Prime minister’s visit to Kedarnath and Badrinath joined a record number of 41 lakh pilgrims that thronged the shrine thereby causing an immense pressure on the natural resources which was unsustainable at any point of time. The roads in the geologically sensitive region should have been five meters wide, but the government widened the roads to 12 meters in a complete disregard to the Ravi Chopra committee recommendations. This led to not only cutting around 50000 trees but also more and more cleaning of the hills. This made the already ecologically sensitive region highly vulnerable to landslides as the top layer was cleaned for the road construction. Another factor which was extremely important in destroying the local hill ecosystem was the establishment of Tapovan-Vishnugad hydeI project which mandated NTPC to carve out a 12 kilometre tunnel puncturing some of the acquirers in the process. However, due to the unavailability of solid rocks underneath, the water released from the acquirers seeped into the soil and loosened it from within. With the top surface of the soil already gone due to intense- construction, the region stood on the edge and sunk as the time passed on. That is not all. In the last decade:, the ridge that houses Joshimath has been traversed by running streams with a high gradient from Vishnuprayag, a confluence of the Dhauliganga and the Alaknanda rivers. The confluence has survived two big glacial and cloud outbursts that deposited heavy sediments causing major erosion in the region. The outbursts brought debris worth 10,000 houses in one day, which made things worse for Joshimath.

Unsustainable Tourism

Tourism can lead to various environmental problems, such as water pollution, solid waste generation, and depletion of natural resources (Buckley, 2012). Therefore, it is important to find a balance between tourism development and environmental conservation by adopting sustainable tourism practices. Many studies have raised concerns regarding the state’s capacity to accommodate tourists sustainably, with estimates suggesting that the maximum capacity of Uttarakhand lies between four and five crore tourists per year (Bhandari, 2017). According to the data released by the Uttarakhand government, the state has witnessed a surge in tourism, which 3.2 crore tourists visiting in 2019, as compared to 2.85 crore tourists in 2018 (Uttarakhand Tourism, 2021). However, increasing visitors have posed several challenges to the state’s infrastructure, transportation and environment. The sinking of Joshimath has highlighted the issue of infrastructure development and its impact on the environment, in Uttarakhand. A study by (Pandey et al , 2015) found that the tourism industry in the Himalayan region has a negative impact on the Himalayan ecosystem in terms of affecting its biodiversity, resulting in habitat fragmentation, pollution, glacier melting, soil erosion, etc.

Discussion

Due to earth subsidence that caused 561 homes in Joshimath to develop cracks, the Uttarakhand government prohibited development work in the area on January 5,2023 in response to protests from the terrified inhabitants. The geological developments underway in Joshimath should be a case study for every town planner working in the hills. The factors at play in Joshimath are also found co be similar in other cities such as Nainital, Champawat, and Uttarkashi. All these cities are witnessing rampant construction, deforestation, tourist boom, and poor civic management. The only silver lining is that they are not on top of ancient glacial debris. The National Institute of Hydrology (NIH) has published a report called “Sinking Joshimath” which reveals that Restriction in the flow of water in Joshimath, Uttarakhand may have led to the major land subsidence in the region early in January,2023. The report further says that the recharge area held an estimated 10.66 million litres of water, which was emptied in approximately one month. To gather this this much water, it might take approximately 12 to 15 months. While the reason for the water flow is not known, there is a possibility that it may have collected due to the blockage of a sub-surface channel and burst from a weak spot. Although not specifically stated in the NIH document, it has been observed that Joshimath had experienced heavy rainfall, which was measured at 190 mm in 24 hours in October 2021 about 15 months before the torrential flow of water started in JP, Colony. There was also flooding in the area on this day. It is feared that rainwater may have collected underground and came out the most weaker points due to the hydraulic pressure. The report explained through maps that the water channels flowing from the, upper areas have disappeared in the middle. Therefore, permanent surface channels will have to be built to dispose of water coming from the-upper areas. The water requirements of local people and flora and fauna should be kept in mind before the channelization of water. Water coming from upper areas and city waste should be disposed of safely. The NlH made note of the necessity to pinpoint both cities with geological settings and specific geographic locations, such as Joshimath. These towns ought to have the tools required so that pre-emptive actions can be done well in advance in order to stop repetitive catastrophe of this magnitude. In the last 46 years from 1976 to 2023. There have been many studies on Joshimath and its surrounding areas. Among them, the 2006 report of Swapnamita Chaudhary, the 2012 Disaster Management Report of the Government of Uttarakhand, the report of the High-Power Committee formed under the chairmanship of Ravi Chopra after the 2013 tragedy, the 2022 report of Piyush Rautela, and the. report of SP Sati, Shubham Shamra and NavinJuyal filed in the same year, are some of the important ones. Apart from this slew of government studies, studies by independent researchers and institutes were also done from time to time. The oldest of all these reports, the 1976 Mishra Committee report which was submitted way back in 1976 has a set of very valid and relevant recommendations which are not at all addressed in true spirit. The Mishra Committee attributed the land subsidence in Joshimath to felling of trees. He recommends that trees are important as they act as mechanical barriers to rain, increase the water conservation capacity and hold the loose debris mass. An increase in grazing and browsing incidents is akin to felling. Natural forest cover in the Joshimath area has been mercilessly destroyed by a number of agencies. The rocky slope is bare and treeless. The absence of trees results in soil erosion and landslides. There is nothing to hold the detaching. boulders. Landslides and slips are the natural outcomes. However, the amount of attention paid to this recommendation can he gauged from the fact that 58,684 hectares of forest land, a little less than the size of Mumbai city, in Uttarakhand was diverted for non-forest uses, mainly road construction, power generation and its transmission between 1991 and 2021. Of these, Chamoli district, in which Joshimath is located, is the district that has diverted the maximum forest land after Tehri Garhwal (ISFR 2021). It is not just about one study; many studies were conducted but they didn’t help the people of Joshimath. Instead of implementing their recommendations, they were ignored. As a result, the- people of Joshimath and Uttarakhand are suffering. Ignoring the recommendations of the Mishra report, there were blasts in tunnels, the govemment was building huge guest houses and private players were also given permission for such buildings. Even after all those suggest ions, the Rishi Ganga and Tpovan projects were continuing and 12 more hydroelectric projects were approved.

Indifferent Courts

With regards to the situation worsening in Joshimath, local organisations and people approached the Supreme Court on January 10. The Supreme Court dismissed the petition saying that the Uttarakhand High Court is already hearing the matter related to the incident in question and the petitioner should approach the High Court. Earlier, following the Chamoli floods in 2021, which claimed nearly 200 lives and caused extensive damage to the Tapovan power project five residents of Chamoli petitioned the Uttarakhand High Court to cancel the environmental clearance granted to the Tapovan-Vishnugad and Rishi Ganga projects and compensate the local people for the damage they suffered. The court not only dismissed this public interest litigation (PIL) but also imposed a fine of 10,000 rupees each on the five petitioners.

Conclusion:

The most recent census survey for Joshimath town was conducted in 2011, revealing that the town is divided into nine wards. According to the survey, the total population of Joshimath Nagar Palika Parishad was 16,709, with 9988 males and 6721 females. as reported by Census India in 2011 . However, recent census data is not available but the population has gone up multiple times. Population and unplanned growth have led to irreparable damage to the ecosystem. In 2006, the number of buildings in Joshimath town was 2456, covering a corresponding area of 4,66,438 sq. meters, and in 2023, the number of buildings in Joshimath town increased to 5113, covering a corresponding area of 8,98,843 sq. meters. Construction in a mountanious region can be challenging due to the rugged terrain and hazard risk, which emphasizes the need to consider factors such as slope stability, erosion, and the impact of natural disasters such as earthquakes and landslides before planning permanent structures. Any country who does not learn a lesson from its own mistake gets obliterated. A study was carried out to understand the deformities occurring in the year 2016-17, 2018-19, 2020-21 and 2021-23. The results revealed that the Joshimath region experienced the highest land deformation during the year 2022-2023. During this period, the maximum land subsidence was observed in the north-western part of the town. The maximum Line of sight (LOS) land deformation velocity +60.45 mm/year to + 94.46 mm/year (2022-2023) occurred around Singhdwar, whereas the north and central region of the Joshimath town experienced moderate to high subsidence of the order of +10.45 mm/year to + 60.45 mm/year (2022-2023), whereas the south-west part experienced an expansion of the order of 84.65 mm/year to -13.13 mm/ year (2022-2023). Towards the south-east the town experienced rapid land subsidence, -13.13 mm/ year to –5 mm/year (2022-2023). ln the 19th century, many terrible Hoods devasted the lives and livelihoods of thousands of people in Switzerland. Between 1850 and 1900, There were nine major floods in the European country, with the most damaging ones in 1850, 1860, 1971, and 1874. After the flood of 1868, professors Elias Landolt and Curl Culmann of the Swiss Forestry Society convinced the government and public that the devasting floods were the direct consequences of unscientific deforestation and the over-exploitation of forest resources. The Swiss, govermnent enacted a special policy and development strategy for the Swiss mountain ranges. This culminated in the formation of the Swiss National Park in 1914. It was the first national park in Europe, with a total area of about 14,000 hectares (about 34,600 acres). Some scholars believe that the flood of 1868 changed Switzerland, resulting in the country that suffered from natural disasters in the 19th century being at the top of the global human development index list in 2024. The Indian situation is quite opposite to these countries. India stands at 176th position out of 180 countries in the environmental performance index. 2024 and 134th position out of 193 countries in human development index list in 2024. The forest bureaucracy has failed to understand a simple thing which even an ordinary person from the Alaknanda Valley could trace a direct relation between the massive flood and indiscriminate deforestation. The lndian hill states ecology is declining very fast on account of unsustainable growth. The hill states are geologically susceptible to landslides. The Himalayas are continuously growing due to the continuous movement of geological plates. Infrastructure development plans in this area are not free from risk. Hydropower projects are also sensitive to the geography of the region. A large amount of water is collected at one place, which increases both the humidity and the pressure in that area which may cause earthquakes. Due to increasing humidity, the risk of landslides also remains constant therefore, before starting any infrastructure development project in the future, environmental impact assessment needs to be properly and thoroughly conducted, else Himalayan states may witness the same fate as witnessed in Uttarakhand and Sikkim in recent past.

Widening of roads, big power projects and other developmental activities have made the Himalayan region very unstable and as a result of this, even small accidents were resulting in huge human and property losses. The example of Himachal Pradesh is very revealing and despite of the fact that the truth is in public domain the successive governments are carrying out with the unsustainable developments. Himachal Pradesh has a total build-up area of 866.14 sq.km (Prashar, 2023). Geographic Information System and visuals showed that most of the build-up area comes under high risk area. Of the total 1,628 km of national highway roads in the state, 993 km are in highly sensitive areas and 514 km of roads are in the low risk areas. Further, 10 sq.km of roads are in very sensitive areas. Apart from this, out of 2,178 km of roads in the state highway, 1,111 km are in high risk areas and 873 km are in low risk .The hydropower sector is also under threat Out of 118 big power projects ranging from 101 to 1,500 MW in Himachal. 67 come under hazard risk and 10 mega power projects fall in the medium and high category for landslides. It may he noted that the state’s biggest power projects, 1,190 MW Karchham Wangtu 1,500 MW NathpaJhakri and 1,325 MW Bhakra are also in sensitive regions. Around 40 percent of the area in Himachal falls in the highly sensitive category and 32 percent in the highly sensitive category (Building Material and Technology Promotion Council). Similarly, Char Dham Highway project is one of the primary reasons behind the increasing number of landslides in Uttrakhand, including the land subsidence reported in Joshimath. A strange rule in July 2022 was framed which says that Highway projects related to defence and of strategic importance in border states were sensitive. Guidelines for these projects should be implemented keeping in mind the strategic, defence and security considerations in each case. lnstitutions implementing such projects in border areas were, thus, exempted from the requirement of Environmemt Clearance (EC) subject to a specific SOP therefore, the path was cleared for the Char Dham highway project The subsidence in Joshimath was so severe that it sank at a pace or 5.4 cm in just 12 days between 27th December 2022 and 8th January 2023 (ISRO report 2023). The study of rocks in the Char Dham Highway project where blasting was undertaken shows that the project is responsible for many of the landslides that have been occurring in the recent past. TotaGhati is a location in Joshimath, Uttarakhand, where there have been landslides and other issues with the road. TotaGhati, where there are seemingly stable rock slopes had a number of slope failures recently. The narrow stretch of TotaGhati is dominated by limestone and interbedded shale rocks, shattered light grey dolomite, with occasional pockets (as fracture filling) of gypsum and purple grey shale and limestone. This is called a ‘Karol formation’ in geological terms. The calcareous (calcium containing) rocks are highly jointed (two to three sets of intersecting joints), fractured and sheared due to three ‘thrusts’ passing proximally to Bayasi, Shaknidhar, and Teen Dhara. The TotaGhati’s rocks are widely sheared, faulted and fractured. At places, cavities filled with secondary carbonate precipitate have developed in the rocks, as the rocks dissolved locally. The beds around TotaGhati are varied due to folding. However, a dominant dip is towards the road. Geologically, rocks with fractures and joints are highly susceptible to failures, which may be triggered even due to the vibration induced by traffic flow (Pradhan& Siddique, 2019). The Joshimath town lacks adequate sewage systems and drainage channels to sustain its rapid growth in recent years. It originally had nine natural drainages (nalas), but only five of them currently exist. This is because of the unplanned development that has changed the town’s natural drainage pattern. Locals have also reported the subsurface seepage of water starting since 2014. In addition, the rapid seepage of water starting since 2014. In addition, the rapid construction of buildings has obstructed the city’s natural drainage channels (Nalas). Inadequate drainage systems have caused excessive surface runoff and sewage water to infiltrate and seep into the ground, thereby accelerating land subsidence. Further, the flood events in June 2013 and February 2021 also negatively impacted this region. These events resulted in significant toe erosion along the streams of the Alaknanda River in the town’s foothills and led to the formation of landslide zones that further increased toe erosion and slope instability. To prevent land subsidence in Joshimath, a comprehensive drainage system is required, comprising proper infrastructure, slope design, routine maintenance, and efficient waste management. The septic tanks and household wastewater should not be permitted to seep into the ground, and the soaking pits should be sealed.

Instead, sewage water should flow through a sewage line and be deposited in concrete safety tanks that are protected against seepage and located away from areas prone to landslides. To prevent water from infiltrating mountain rocks and causing landslides, drains should be constructed to transport water to safe areas, and cracks should be flled with a mixture of line, local soil, and sand bitumen. Further, in order to mitigate toe erosion and slope instability along the Alaknanda River, retaining walls must be constructed in affected areas to provide lateral support and prevent toe cutting. Therefore, it is essential to acknowledge that the issues the town of Joshimath is facing are not unique to this region. Many other regions in the Himalayas and around the world face comparable environmental and geological challenges because of rapid human development. Therefore, a concerted effort is required to address these issues and promote sustainable development practices that place a premium on environmental preservation. Joshimath’s future depends on the implementation of effective measures to mitigate environmental and geological hazards. Future imperatives include prioritizing sustainable development practices and implementing policies that account for the region’s fragile geological and environmental conditions. The growth of the town should be regulated, and large infrastructure projects should be carefully planned and implemented. Large infrastructure and hydropower projects should be evaluated carefully to ensure that they do not exacerbate existing environmental issues. To prevent further land subsidence, the government should work towards developing an effective drainage system and waste management system while preserving the region’s natural resources and considering the region’s fragile geological and environmental conditions when planning and executing development projects. The vulnerability of the region to natural disasters such as earthquakes and landslides must be addressed, and precautions must be taken to protect the local population. In addition, the government should invest in the development of alternative industries, such as ecotourism and sustainable agriculture, to reduce the region’s dependence on the hotel and tourism industries, which have contributed to land degradation. To ensurethe long-term prosperity and well-being of the region, a cautious and sustainable approach is required overall.